The Past Is Not The Past

‘Tie Dye and Tofu’ explores Eugene’s activist and hippie years

by Suzi Steffen

|

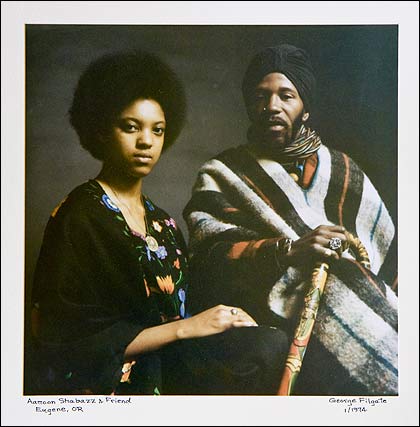

| Aamoon Shabazz & Friend, 1974. Photo by George Filgate. |

|

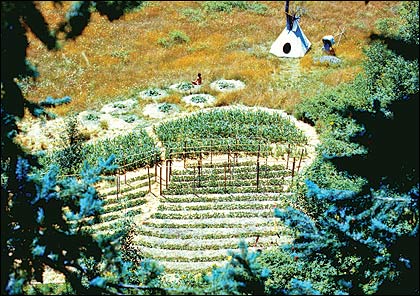

| Butler Green Commune. Courtesy Lane County Historical Society. |

|

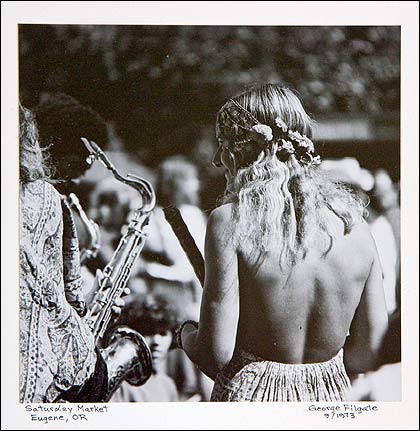

| Saturday Market, 1973. Photo by George Filgate. |

|

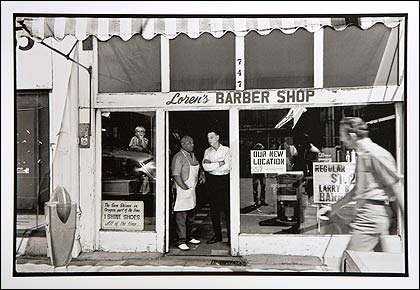

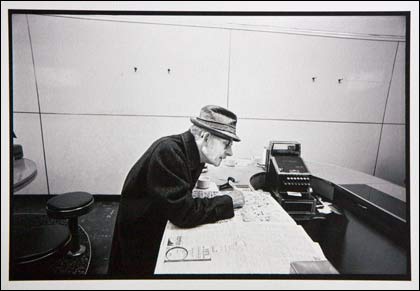

| Loren’s Barber Shop. Photo by John Bauguess. |

|

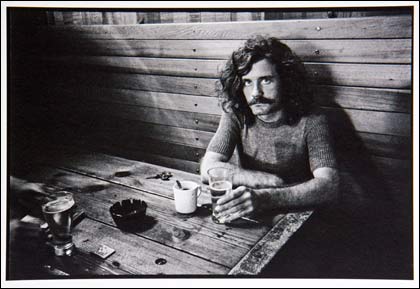

| The Brass Rail Tavern on Willamette. Photo by John Bauguess. |

|

| Pope’s Donut Shop on Willamette. Photo by John Bauguess. |

|

| Kirstin Simon painting the VW bus. Photo by Trask Bedortha |

The visitor, a middle-aged woman, spat the question out with disgust.

“Why are there so many hippies around here?” she asked Mary Dole, the exhibits coordinator at the Lane County Historical Museum.

Dole, who’s lived in Eugene most of her life but who has also traveled and lived in various places around the country, thought the woman had a good question, albeit a rather hostile tone.

Other places, including most college towns in states from New York to California, had their share of activists and hippies in the ’60s and ’70s. They had their Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; they had their Students for a Democratic Society. They had their civil rights, women’s rights, gay liberation, Black Panthers, Gray Panthers, anti-war protesters, nuclear disarmament marchers, American Indian Movement, free day cares, free breakfasts, cooperative housing and businesses, ride boards, coffeehouses, head shops, craft cooperatives, food cooperatives, macramé classes, free love-ins, be-ins, sit-ins, lie-ins and their tensions between the political and the social wings of the movements sweeping the country.

Eugene had Ken Kesey and Cynthia and Bill Wooten. Oregon had quite a lot of high-quality pot along with land for communes and an ethic that we now call DIY. Beyond that, Eugene had something special — and that something stuck in ways that permeate the air of the town and the political and emotional lives of residents through today, 40 years after the first Saturday Market and the first Renaissance Faire (which became the Oregon Country Fair).

All of it, or as much of it as almost 100 Eugene residents could tell the Lane County Historical Society and as much of it as can fit into the exhibit space at the museum, will be on display at the museum’s “Tie Dye and Tofu: How Mainstream Eugene Became a Counterculture Haven,” which opens with a big celebration Saturday, May 8, and stays up for almost a year.

“I want to go see the show,” said Saturday Market manager Kim Still. “I was a kid, and I have amazing, fond memories of the whole thing.”

The exhibit, which was still under construction Tuesday morning, contains different areas to mark the multitude of different strands making up all of the social change in Eugene, and the world, between 1965 and 1975.

One strand, which Still remembers well because her dad was an art teacher at South Eugene High School, was the crafts movement, a way to get art-making into the hands of anyone who wanted to put in a little time and energy. Roger Beck made house trucks, owns the site housetruck.com and published a book about house trucks. He made his living selling wire jewelry, beginning with the first Saturday Market at 10th and Oak in 1970. He said that Eugene eventually became a crafter’s dream. “There were all of these little craft stores around, and the (Saturday) Market got very established,” he said.

In the show, Mary Dole said, a section they’re calling “the hippie pad” will help honor that spirit by showcasing macramé plant holders and other crafts of the time, including, yes, tie dye and probably batik as well. But that’s only one side of the upstairs portion of the show. To create the feel of mainstream Eugene at the time, Dole and her interns asked St. Vincent de Paul to keep an eye out for 1970s-style appliances for a recreated kitchen. The avocado green refrigerator and stove, brown sink and era-appropriate cupboards give visual heft to the jolt of nostalgia that permeates this recent history show. Nothing in the kitchen looks out of place, ranging from little touches like a cookie jar with mushrooms painted on it to Tupperware containers in the basic avocado and orange.

But before visitors get to the crash pad or the place where they learned to cook brown rice and to season tofu with nutritional yeast, they’ll see much more downstairs,

The story begins with a section about political identities. Designed by Dole and intern Kaley Sauer, the wall plaques — which happen to be both functional and quite, quite lovely — in that area tell the stories of the movements sweeping the country and having an impact on Eugene. Those who lived through the time as students, professors or just city residents can read in detail about the times a-changin’ so fast it was hard to keep up with everything. For those who weren’t alive during the time period and never had a history teacher (or textbook) who could adequately explain what was going on, this section will provide swaths of information that might help some pieces fall into place.

“We hope it’s intergenerational,” said Bob Dole, the historical society’s executive director. He believes that people who were young at the time can bring their grandchildren, that the exhibit will spark conversations and lead to a fair amount of learning.

One of the most exciting parts downstairs will be a re-created coffeehouse. The Odyssey Coffeehouse at 713 Willamette was one of the centers of counterculture life in Eugene for years. “It was pure hippie,” Beck said — and that wasn’t because of its dark roast or its lattés. The space gathered people with a vast range of energy and ideas about what Cynthia Wooten called “an alternative way of being alive.”

At the same time, as anti-war activists, draft evaders on their way to Canada and formerly mainstream refugees from the East Coast gathered to listen to jam sessions with the band Wheatfield, downtown’s mainstream life went on all around them. Photographer John Bauguess documented that particular block with rigor and with gorgeously framed shots, and his images of the people in the Odyssey as well as those in Pope’s Donut Shop and Loren’s Barbershop richly illustrate pre-urban renewal buildings and the look and feel of the times. Dole said that Bauguess loaned a huge collection of photography for the exhibit, and our cover shows the warmth and formal skill of one of his many snapshots of downtown Eugene’s changing ways. Journals will sit on tables and invite more participation in the coffeehouse section of the show, Dole said.

One of the keys to the show has been public participation, Hart said. “This is only the second time we’ve gone to the public to ask for public assistance,” he said. “It’s different from the traditional museum style, where we’re the experts and we tell everyone what’s important. This is democratizing the museum field.” That’s one reason the show doesn’t emphasize personalities like Kesey but instead talks about “the story of common folks,” Hart said.

The common folks’ stories include documents from those who took part in Butler Green Commune, one of the closest back-to-the-land experiments to Eugene. Some of that ethos still prevails in Eugene with organic food markets and an emphasis on small farms as well as a do-it-yourself (preferably in community with others) ideal for creating enough food, land and health for everyone.

More documents of the era came from the alternative press. Long before What’s Happening (which evolved into Eugene Weekly), alternative papers filled the coffeehouses with information that mainstream papers and news sources weren’t in the business of sharing. Country Fair documenter and The Fruit of the Sixties author Suzi Prozanski gave her time and expertise to helping create this show (some of the wall plaques bear her writing), but she also loaned the museum a treasure trove of issues of the main Eugene alternative paper, The Augur. The Augur, Dole said, was more than just another alternative paper; it lived by its radical politics. “They didn’t mind doing things like uncovering narcotic agents and revealing their home address,” she said. An entire section of the exhibit covers the alternative press in Eugene, especially The Augur, and demonstrates how information spread through hand-cranked copiers and hastily filed stories from actions around the country.

Those narcotic agents the paper exposed were around because of the popularity of drugs in some counterculture lifestyles, of course, and the show acknowledges that with a nod to the Crystal Ship, a head shop and record store that served as one of the centers of social life. In the “Entrepreneurs and Endeavors” section of the show, visitors get a sense of the ferment of small, idealistic businesses and nonprofits that sprang up everywhere. Some of the lasting legacies of that time include Toby’s Tofu, the White Bird Clinic and, of course, both the Saturday Market and the Oregon Country Fair, which recently voted to help fund the show.

“This show has been expensive!” Dole said, and that’s despite both the long list of exhibit donors and a large dose of design help and consultation from Alice Parman and her UO exhibits design class. But Dole dreams of doing more, trying to get oral histories from the people who come through the exhibit and who contributed to the exhibit. Dole’s family moved to California for a year, and when she returned for her senior year in high school at the end of the 1960s, she said, Eugene was different. “In my memory, there wasn’t much going on when we left, but when we came back, the change was very evident,” she said. “Why did it change? And why did it stay?”

Roger Beck agreed that Eugene exploded with change (quite literally in several cases; the UO’s ROTC building burned down, and someone bombed the UO’s Prince Lucien Campbell Hall in 1970), but the rest of Oregon had a lot of counterculture life sweeping through at the same time. Beck said that elsewhere, it didn’t quite stick. “If you think about it, it didn’t happen in Corvallis; it didn’t happen in Roseburg,” he said. “In southern Oregon, there were all of these communes. It was hippie versus redneck down there.”

But Eugene had everything ranging from Sundance Natural Grocery to head shops and community resources. “All of these alternative things were available to you here, and they weren’t in other places,” Beck said.

Everyone has theories about the stickiness of Eugene’s alternative communities, the way that places like the Saturday Market became a valued institution in Eugene’s cultural life. Many of those theories add up to one basic idea: Eugene’s still part of the frontier. Kim Still, who’s seen the Saturday Market from its early days when she was a kid through its popular, Etsy-tinged status today, said that many people she works with tell her that “they’re either the black sheep of the family, or they’re getting as far away as possible from whatever it is, the establishment or whatever.”

Mary Dole, like Still, grew up here and has lived in Eugene for much of her life. She shares Still’s theory, but with a slightly different twist, one that might be expected from someone who works at what used to be called the Pioneer Museum. Traditionally in U.S. history, Easterners and Midwestern people come to the West to make a fresh start, she said. That was true for a lot more than those who homesteaded in Oregon. “The frontier’s in the subconscious of the U.S.,” she said, “People think of it as opportunity, and that’s what people are doing here.”

UO students working on some of the exhibit pieces have made some discoveries. “I’m not from Eugene,” said Lindsey Cranton, who’s helping paint a 1965 VW van that will be a centerpiece of the show. The students had to compile a lot of research to understand what kinds of designs the van should sport. “We found a lot of really cool things,” Cranton said. “I didn’t know a lot of this happened. It’s made me like the city.”

Still said, “There’s got to be someplace where people can flee to and be free.”

Find out more — much, much more — on opening day, when Wheatfield plays at the coffeehouse and visitors can try their hand, again, at tie dye, from 1-4 pm Saturday, May 8. The show remains up through March 2011. More info at http://wkly.ws/ji

And don’t forget to visit A’kasha (The Fifth Element) in Beaverton to see Eve Crane’s photos of the Black Panthers. That show begins at 3 pm Saturday, May 15, with an artist presentation and with Black Panthers founder and author David Hilliard, who will sign his most recent book. The show opens to the general public Monday, May 17. More info at http://wkly.ws/jh