Philando Castile, Alton Sterling. And before them Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Tamir Rice and Sandra Bland. Those are among the names we know, whose cases in the last three years came to media attention because a video of their deaths went viral or the protests were loud enough to finally draw the lens of the media.

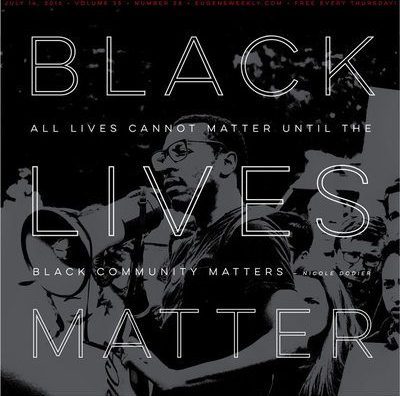

Black Lives Matter.

For many, the knee-jerk response to that is, “All Lives Matter.”

The national Black Lives Matter organization says in addressing some of the many misconceptions about the movement that “the statement ‘black lives matter’ is not an anti-white proposition.” Black Lives points out that there is an unspoken but implied “too,” as in “black lives matter, too,” when you say, “black lives matter.”

Or as still others have pointed out, when you say, “save the whales” you are not saying, “screw the dolphins.” Saving the rainforest does not mean you want to see Oregon’s old growth cut down.

Oregon is a historically white state — largely due to a history of laws that prevented African Americans from owning land and allowed “sundown towns,” meaning while blacks could pass through, they could not stay after sunset. Eugene itself was a sundown town, if not by law then by practice, according to researcher James Loewen, author of the book Sundown Towns.

In 1848, while still a territory, Oregon’s provisional government passed a law forbidding black and mixed race people from living here.

Oregon didn’t allow interracial marriages until 1951, the same year it stopped applying insurance surcharges to nonwhite drivers. One of the first black-owned house in Eugene was purchased in 1948 — less than 70 years ago — by C.B. and Annie D. Mims, but it was bought under the name of Mims’ white employer.

As of July 2015, Lane County has an African American population of just 1.1 percent, compared to 13.3 percent nationally. According to the Partnership for Safety and Justice, “African Americans in Oregon are six times more likely than whites to be incarcerated” and “African Americans constitute 4 percent of Oregon’s youth population but 19 percent of the state’s Measure 11 indictments among youth.” Measure 11 crimes call for mandatory minimum sentencing.

In Eugene, according to the most recent 2013 police use of force review by the police auditor, “We found no pattern among individual officers using force against minorities.”

Some look at such statistics and erroneously argue that blacks are more likely to commit crimes. However, according to a real-time database launched by The Washington Post last year to track police shootings in the United States from the beginning of 2015 to now: “U.S. police officers have shot and killed the exact same number of unarmed white people as they have unarmed black people: 50 each. But because the white population is approximately five times larger than the black population, that means unarmed black Americans were five times as likely as unarmed white Americans to be shot and killed by a police officer.”

Five times more likely to be shot and killed.

So how does white Eugene show that we understand black lives matter?

Kristi Wallace, a long-time Eugene resident who now lives in Bend, tells of a recent visit to her doctor.

“Hey, you’re my only black patient,” he said to her, referring to the recent killings of Sterling, Castile and five Dallas police officers. “How has it been for you?”

“Weeping,” she says, “I told him the truth.”

Wallace says, “I told him that cops killing blacks is just part of the story for me. That for me and mine, pervasive, ugly racism exists far beyond the sound bites and cell phone playback. I looked him in the eye. Told him about how I, and every one of the people in my black family, have had whites — police and civilians — act out rage and racism all over us, repeatedly, in more than one country, in more than one language, over my entire lived life. I told him that I am tired.”

Wallace says, “I’m not an activist.” She told her white doctor she is “just one black American who is disgusted by the violence directed toward my people. And now all people are my people. I want the slaughter to stop. It doesn’t matter who is holding the gun. It only matters that it stops. Now.”

“I’m so brokenhearted,” she told him.

“Me too,” her doctor said, and then, Wallace says, he wept.

Update

Heather Kliever of the Lane County Historical Society says that Eugene’s first documented black owned house was that of Wiley Griffon (also spelled Griffin and Griffn) who would have come to to the area around 1888 and died in 1913. His home was located near the Millrace in the area of the Eugene Water and Electric Board building. Douglas Card writes of this in his book from Camas to Courthouse.