A former University of Oregon public safety whistleblower, James Cleavenger, who won nearly $1 million from the university in 2015, is running against incumbent Patty Perlow for Lane County district attorney.

The election is taking place as COVID-19 brings new challenges to the DA’s office. It also brings up questions about election donations, rural policing, the Voters’ Pamphlet and a reminder of the case known as the “bowl of dicks.”

Perlow has been with the office for 30 years, having served as chief deputy district attorney before being appointed DA in 2015 and later successfully running for the position in 2016.

Because of the Lane County Public Service building’s physical layout, she says, staff are unable to maintain a 6-foot distance and have had to switch to a split schedule.

“I’ve worked with the public defender to get the court to move to remote hearings,” Perlow says. “The future challenge is going to be to process all of the cases that are on hold now.”

Money Talks

The largest campaign contribution Perlow has received this year was $3,000, from Wildish Construction Co. In total, she has $43,639, compared to Cleavenger’s $106,640.

Cleavenger’s campaign treasurer, Kyle Lakey, met Cleavenger while also working as a UO public safety officer in 2013. In March, Lakey donated $50,000 of his own money to his friend’s campaign. He then loaned him another $50,000. This is the first and only time Lakey has donated to a political campaign. According to Cleavenger, Lakey is “independently wealthy.”

“I chose to donate $50,000 and loan $50,000 to his campaign for DA because, as a former officer and a citizen, I am perpetually frustrated by the rate of recidivism directly caused by the lack of will the current District Attorney’s Office possesses to prosecute crimes, especially in small towns,” Lakey says.

“I’ve got over $100,000 in my campaign war chest,” Cleavenger says. “It’s not like I’m getting money from George Soros or some corporation. I have way more individual people donating to my campaign than she does. I’m used to being the underdog, and I think I can win.”

While Cleavenger can say he didn’t receive donations from large corporations, campaign finance records show Perlow has more individual donors than Cleavenger.

Law & Insurance

Cleavenger says he first gained experience in politics while working on the advance team as a motorcade driver for then-Vice President Al Gore in 2000 in Chicago. Originally from Richland, Washington, Cleavenger graduated UO law school in 2008 before working as a public safety officer for the university from 2010 until 2013. Since then, he’s worked as a reserve police officer for several cities near Eugene, including Junction City, Coburg and now Oakridge.

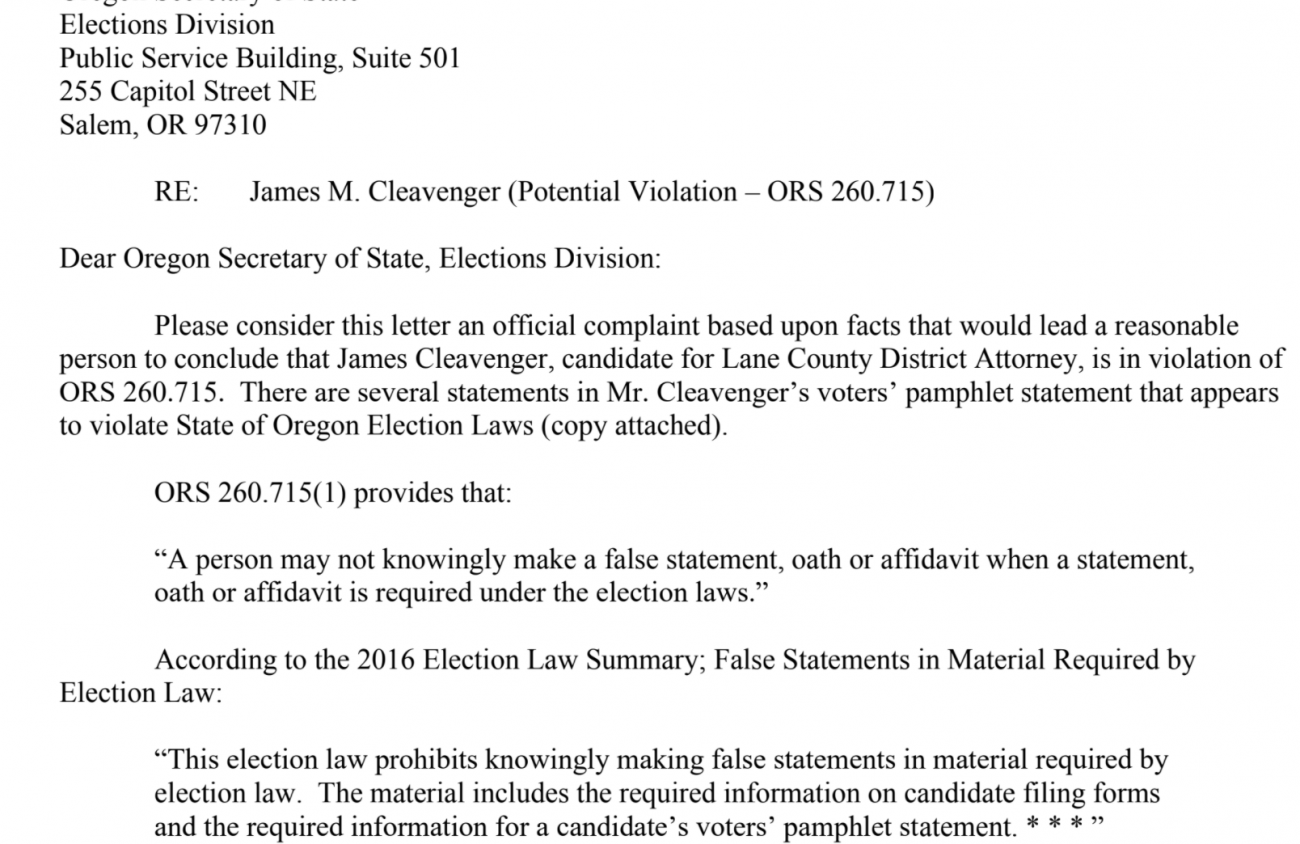

On Monday, April 20, retired Lane County Sheriff Byron Trapp filed an official complaint with the Oregon Secretary of State office, alleging that Cleavenger misrepresented himself as a practicing lawyer in order to win votes in the upcoming DA race.

Cleavenger told Eugene Weekly that he was a part-time lawyer not currently accepting clients. His campaign website also presents him as a licensed lawyer. However, to legally practice law in Oregon, an attorney must purchase annual liability insurance. According to documents from the Oregon State Bar, Cleavenger has been exempt from purchasing insurance due to filing as a non-law lawyer since 2018.

“Cleavenger has told the state bar association that he doesn’t need to comply with Oregon law rules on having liability insurance because he isn’t currently practicing law,” Trapp says. “But then he files to run for DA as what appears to be a practicing and active attorney. And so one of those can’t be accurate. They both can’t be accurate at the same time.”

According to documents provided to EW Cleavenger purchased liability insurance on April 1, 2020. However, for the past three years Cleavenger says he had been practicing law under exemptions that allowed him to avoid paying liability insurance; that he’s only acted as an “of counsel attorney,” which is defined as a lawyer who has a relationship with a law firm, but is neither an associate or a partner.

“I have my doubts that Mr. Trapp himself wrote this letter,” Cleavenger says. “The allegations are not true. I’ve never practiced law illegally. I’ve practiced law under exemptions including the same exemptions as Patty Perlow.”

Perlow lists her occupation in the voters pamphlet as “district attorney.”

Trapp’s complaint follows a similar one reported to the Oregon Bar Association by attorney Rohn Roberts.

Small Town Blues

A majority of Cleavenger’s police experience comes from his work as a reserve police officer in the Lane County towns surrounding Eugene. He’s currently based in Oakridge.

“In all these communities, everyone complains to me that the DA doesn’t prosecute cases from small towns,” Cleavenger says. “They just seem to not care. And I used to be a defender of the DA’s office because, you know, I’m a lawyer.”

Perlow told The Oregonian in February that she spoke with Oakridge city leaders late last year to raise concerns about the quality of police investigations in the small town. Perlow says in the article that Cleavenger was involved in “a majority of the cases that we were bringing to their attention.”

Perlow says her department has four investigators, three of whom are grant-funded, doing follow-up work on more serious cases. However, Perlow also acknowledges the limitations when it comes to prosecuting cases from surrounding districts.

“Smaller jurisdictions with small police departments have small budgets,” Perlow says. “Recruitment and retention is a huge problem. Training is limited. So the investigations are not always complete. We do file all provable cases.”

‘Bowl of Dicks’

Cleavenger is probably best known for winning a $755,000 jury verdict in the “bowl of dicks” case against the UO Police Department, after claiming he’d been unjustly fired for speaking out about bias and unfair treatment. Including the $500,000 in attorney fees, the school ended up paying over $1 million to settle Cleavenger’s legal claims.

In the federal case, Cleavenger and his attorneys alleged that the former chief of UO’s police department, Carolyn McDermed, and two other department managers had fired Cleavenger in retaliation for whistleblowing. One of the central claims of the case is that several UO officers maintained a “bowl of dicks” list, which featured the names of people the participating officers disliked and wished would eat a bowl of dicks.

“It destroyed me for a while,” Cleavenger says. “I was lucky enough to have a law degree to fall back on. But it took three years. Luckily, justice was served, and it strengthened my faith in the justice system.”

Perlow and Cleavenger agree that the DA’s most important goal is to keep people out of the criminal justice system. This can be done by expanding treatment court programs and addressing what Perlow calls Lane County’s mental health crisis.

“We need a 24-hour crisis center. We need more programmed housing. We need to start earlier with smarter strategies to keep kids safe and in school,” Perlow says. “We need more law enforcement in the rural areas. Our highways are dangerous. My office is part of the whole public safety system; the criminal justice system is just one component of public safety.”

The district attorney’s race will be on the May primary ballot.