By Joanna Mann, Jennah Pendleton, Addie Peterson and Silas Sloan

Eugene officials have forced unhoused people to move from their campsites more than 1,600 times since the COVID-19 pandemic began, flouting federal health guidelines intended to keep people without permanent shelter safe from infection.

An analysis of city records obtained by Eugene Weekly and the Catalyst Journalism Project shows that Eugene’s clearing of homeless camps during the pandemic has been far bigger and more intensive than has been previously reported.

City officials uprooted unhoused people at a rate 40 percent higher than they did in pre-COVID days — without providing most of the people whom they forced to move with meaningful housing alternatives.

The city’s actions stand in stark contrast to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines cautioning against uprooting unhoused people during the pandemic without adequate shelter for the people displaced.

CDC guidelines say having unhoused people live outdoors may not provide the best option for their overall health, but that during the COVID-19 pandemic, doing so might be the safest choice. “Outdoor settings may allow people to increase physical distance between themselves and others,” the guidelines say.

“Connecting people experiencing homelessness to permanent stable housing should continue to be the primary goal,” the CDC adds. “However, if individual housing options are not available, allow people who are living in encampments to remain where they are.”

Eugene officials have sought to keep the public focused on highly visible encampments of unhoused people that have grown in downtown, neighborhoods and city parks. These encampments draw complaints, generate controversy and attract news media attention.

But the records obtained by EW and Catalyst reveal the city’s hidden history of how it dealt with the homeless during the pandemic.

The records show that in 2020 city officials — while focusing public attention on large encampments — launched a sweeping seek-and-expel mission against lone campsites, targeting one unhoused person and one tent at a time.

While an encampment might include anywhere from 10 to 30 people, the city was also quietly forcing about 50 campsites a week to move during the last half of 2020, city records show.

Tristia Bauman, senior attorney with the National Homelessness Law Center, says local officials should take the CDC guidelines seriously as a way to prevent the spread of COVID.

“It is true that CDC guidelines are not binding law, but they exist for the purpose of protecting public health,” Bauman says. “The CDC is not a body that just offers opinions about approaches to homelessness. They issue guidance about approaches to outdoor encampments because these approaches matter for public health. We are in the midst of a global pandemic.”

Eugene Mayor Lucy Vinis acknowledges the high rate of campsite removals the city has launched in the past year. She says the city has provided some additional shelter, including temporary microsites, rest stops and overnight car camping sites. Vinis says that the city has since sought to balance the public health risk of dispersing overgrown camps and the public health risk of keeping them there.

“There’s more than one health consideration involved in homeless campsites,” Vinis says. “So we are dealing with a pandemic, and we have relaxed our rules around people sleeping in open spaces, because we are trying to comply with that and reduce the spread of COVID.”

But the result, as city records show, was a stepped-up effort to remove unhoused people who were camping.

Homeless advocates say they were aware that the city had continued to drive out unhoused people who were camped during the pandemic. Former Occupy Medical director and longtime homeless advocate Sue Sierralupe says she has repeatedly asked Eugene officials to change their policy during the pandemic.

“Now that you know that the very basis of your choice is counter to public health during a time of a pandemic, I beg you, stop,” Sierralupe recalls pleading with the City Council. “No, nothing. They kept on going.”

One person not at all surprised by the numbers is Kevin, who has been living in Eugene without a permanent place to live for the past three years.

Kevin, who asked to be referred to by his first name because he fears being targeted by Eugene police, says that he stayed at the Eugene Mission before the COVID pandemic arrived. He decided he would be happier living on the streets and camping out during COVID-19.

Kevin says that in the summer and fall of 2020, the height of COVID cases in Lane County, city officials made him move at least 10 times from approved camping spots like Washington Jefferson Park. He estimates that in around 60 percent of cases this was done through city crews posting a notice, but nearly half of the time the Eugene Police Department made him move despite previously being told by city crews that he and his neighbors were OK where they were.

“Something about having to move every two or three days is unsettling as a human,” Kevin says. “Having to move all the time constantly and never knowing when they’re gonna pop in and say that you have to move is nerve racking, and it really wears on you quick.”

The number of unhoused people living in and around Eugene was approximately 1,606 in January 2020, according to that year’s Lane County Point-in-Time count. It’s a number that has fluctuated in the past decade. Eugene often ranks as having one of the largest homeless populations in the nation on a per capita basis. Many local officials and homeless advocates believe the Point-in-Time census greatly undercounts the true number of unhoused people.

Over the years, city officials have sought to address homelessess by creating new microsites, rest stops and emergency shelter and warming sites. In May 2019, the city and Lane County approved a joint plan to address homelessness and in February 2020 hired Sarai Johnson as the Joint Housing and Shelter Strategist for the city and the county.

She arrived on the job just as the COVID pandemic was starting. Johnson says that the city and county, already with too few beds, lost capacity as shelters had to decrease the space available to account for social distancing.

“We have a lot of beds that are not currently open because of COVID-19. So the shelter capacity is even reduced from what it already was, which wasn’t adequate for our community at all before this all started,” Johnson says. “The reality is that there is no place that has been identified as locations where people are going to be able to be.”

Another way the city has sought to address camping has been to sweep areas where unhoused people have pitched their tents or erected shelters. City code bars camping in city parks, open spaces and rights of way, such as sidewalk and bike paths. Police can ticket people for illegal camping, but most often the city tells campers to pack up and move.

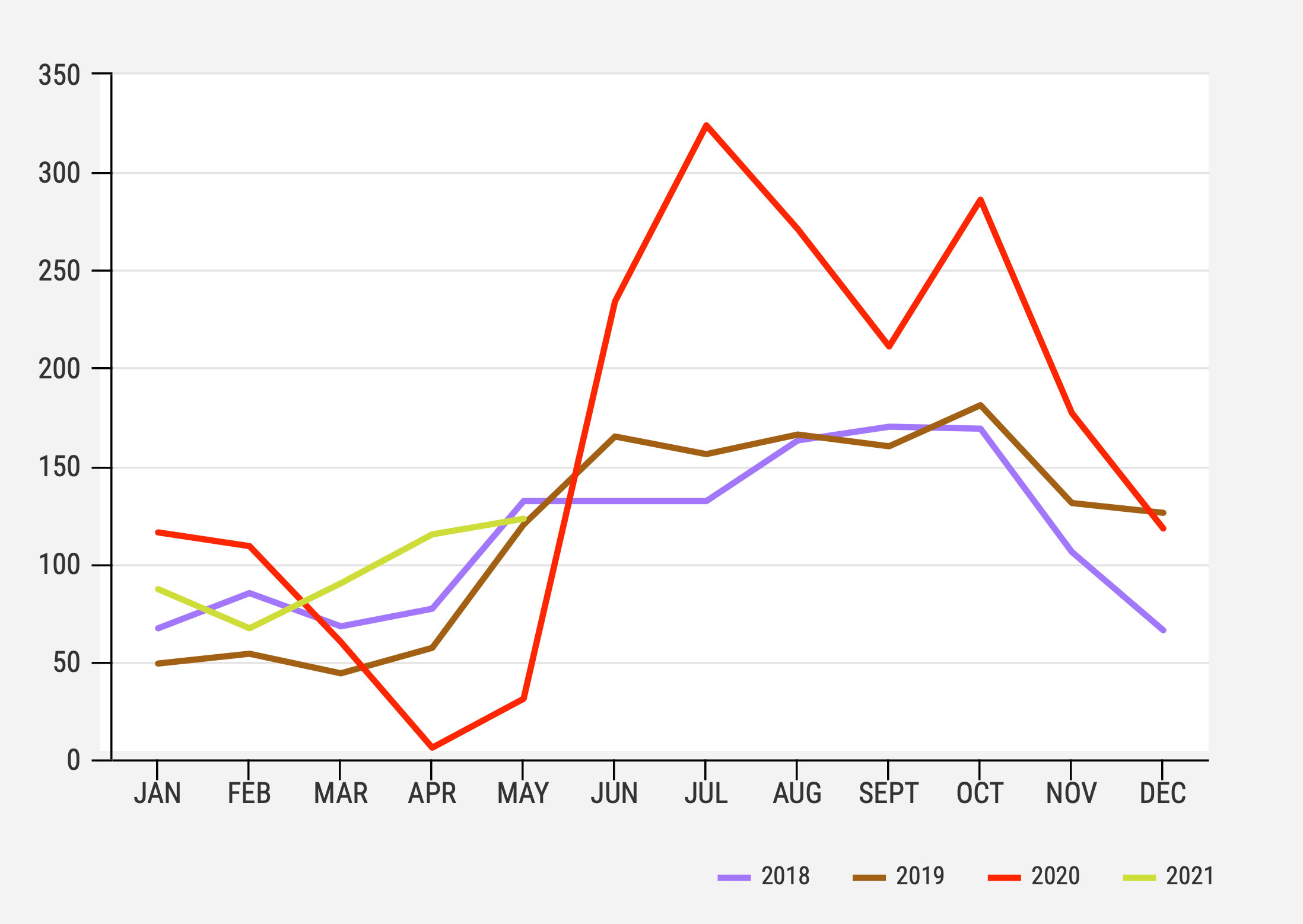

The Eugene Department of Public Works creates a work order for every camp cleanup. Using the Oregon public records law, EW and the Catalyst Journalism Project obtained 6,700 of these work orders from Public Works dating back to 2018.

Records show that in most of the cases, the work orders target a single tent or makeshift shelter, not an encampment. The work is often difficult, sometimes requiring the collection of used needles and other hazardous waste. In some cases, city crews clean up abandoned campsites.

But when crews find an active campsite, they post a “Notice of Scheduled Cleanup,” warning campers that they have 24 hours to move or risk losing their belongings.

In January 2021, the city announced that it would provide a 48-hour warning notice to campers stating what the camp would need to do to meet the city’s criteria for camping. If not met, the city then posts the 24-hour notice of cleanup.

After the initial COVID lockdown, city officials embraced the CDC guidelines and in April and May 2020 backed off from sweeping camps, both large and small. The city allowed larger encampments to form around downtown and all but stopped clearing individual campsites around the city.

At the time, the city’s website cited the CDC guidelines as a standard. As Eugene’s website put it in May 2020, “The City is focused on strategies that support efforts that will ‘flatten the curve’ by reducing the need for people to travel around the community to access basic needs and shelter.”

That attitude changed in June of that year when the city, without explanation or warning, abruptly brought the hammer down on camping.

Officials closed large encampments around the city, citing an increasing number of citizen complaints as more people were out using parks in the summer months. While the first three months of the COVID lockdown provided somewhat of a safe haven for those camping in parks, that all changed when city officials decided in late June they were done waiting.

Temporary emergency shelters created during the pandemic shut down on June 5, 2020, due to reduced shelter capacity and an increase in the unhoused community. Two main shelters, Dusk to Dawn and the Eugene Mission, reduced shelter capacity to nearly half of what it was pre-COVID. Most of the people who had to leave the temporary shelter had no choice but to return to the streets.

During the first three months of the pandemic, March through May 2020, city crews posted eviction notices in front of only 97 campsites, city records show.

Over the next three months, the number shot up to 829.

The city went on to dislodge unhoused people from their camps more than 1,600 times between June and December 2020, according to records examined by EW and Catalyst. The numbers reflect that one person, like Kevin, might be forced to move multiple times. Data recently released by the city on camp show more than 300 more camp removals between January and May 2021.

City officials have suggested that the number of 24-hour notices doesn’t necessarily reflect the number of campers displaced. Their claim: Some campsites might already be abandoned by the time crews arrive and post the notices. But EW examined hundreds of work orders from 2020 and found that the 24-hour notices did indeed force people to move more than 90 percent of the time.

Reporters sought to ask City Manager Sarah Medary, who oversees the city’s response to COVID and the homeless, why the city suddenly stepped up its eviction of individual campers in June 2020, despite what the CDC guidelines recommended. Medary declined four requests for an interview.

Instead of responding to questions or the interview requests, Medary released a statement in April through city spokesperson Laura Hammond. In the statement, Medary said the city now has a temporary system that allows for some camping. But her explanation for why the city cracked down so hard on campers during the pandemic remains unclear.

“In June, Oregon transitioned to a new response phase allowing the City to address campsites that were of greatest concern for the health and safety of the people living in them and for surrounding neighborhoods and businesses. While many campers remained in parks and natural areas, they weren’t gathered in the large groups of tents, they were more disbursed. The number of camps addressed went down following that initial work in June.”

There are two big problems with Medary’s statement when it comes to the facts.

First, the state of Oregon in June 2020 issued no policy changes that dealt with housing or people experiencing homelessness. And at no time did the state issue new policy changes that contradicted the CDC guidelines calling for unhoused people remaining in place when no alternative shelters exist.

We asked Hammond to identify the specific June 2020 policy changes to which Medary was referring. She never responded to the question.

The second big problem with Medary’s statement: She says the city in June 2020 wanted to break up larger encampments so that unhoused campers would be more dispersed.

The city did so — and then quickly moved in to sweep those more isolated camps away.

In other words, the city — without any public explanation — moved from keeping people safely in place, as the CDC recommends, to uprooting them in record numbers.

The city’s Community Engagement Manager Kelly Shadwick says the city looked at the CDC guidelines and determined what their “true intention” was, and made decisions based on that interpretation.

“The CDC is an organization made up of people just like you and me,” Shadwick says. “I think when the CDC makes guidelines for things, you have to look at those guidelines and then see, like, what is the true intention. I think where we’re at now is we’re better following those CDC guidelines.”

In December 2020 an estimated 100 people gathered in an encampment on Oregon Department of Transportation property in the Washington Jefferson Park area. The city signed an agreement with ODOT that allowed officials to force unhoused people to move if city officials thought there was too much trash buildup. The camp was cleared in the first week of December.

In January, Eugene officials, under pressure from homeless advocates, agreed to set parameters that allow temporary urban camping in some areas. While camping remains banned in neighborhood parks, riparian areas and within a certain distance to playgrounds and private property, it is permitted in some areas if campers follow the city’s criteria.

The criteria require social distance, clean spaces with no significant garbage, public access to sidewalks and entrances and no EPD-verified reports of criminal behavior.

The temporary camping allowance came after nine local nonprofit organizations, including Occupy Medical, wrote an open letter to the city asking officials to stop camp clearances during COVID and communicate where people could go in the meantime.

City of Eugene Public Affairs Manager Brian Richardson says if he could go back in time, he would have created the criteria earlier and been more specific about where campers can and cannot be.

“We’re not being human if we say there aren’t things that we would change along the way,” Richardson says. “This is hard. It’s hard for city staff, it’s hard for the unhoused, it’s hard for the housed, there’s so many different needs.”

Work orders show crews have recently been citing reasons to clear out campsites, such as proximity to riparian zones or private property, rather than order camps be removed without balancing the health concerns.

On April 28 the Eugene City Council unanimously voted to adopt a plan that will relocate unhoused people from parks like Washington Jefferson to new spaces deemed safe camping and safe parking spots. These new sites have yet to be established, but the city promises that the sites will have running water, electricity and portable toilets. Mayor Vinis says it will be an “improvement of circumstances.”

“The idea is to increase the degree of safety and the city’s management of those sites, because they would be permitted sites,” Vinis says. “We will make sure their basic needs are met in terms of sanitation needs and water. And we will be staffing, connecting with outreach.”

The Oregon Legislature recently passed HB 3124, requiring officials to give at least three days’ notice before conducting a sweep. The bill is now headed to Gov. Kate Brown for a signature.

Kevin says he is looking forward to not living in constant fear of eviction at the new sanctioned site.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever seen the city trying to work with us instead of against us,” he says.

Weeks after EW spoke with him, Kevin was diagnosed with COVID-19.

Sierralupe worries that the mistrust the city created with sweeps during the pandemic will leave too many unhoused people uneasy about trusting officials when it comes to seeking a vaccine.

“The unhoused survive by being wary,” Sierralupe says. “My hope is that this caution doesn’t end up endangering the unhoused population by limiting their trust in the most reliable barrier we have to COVID-19. Sweeps destroy homes and trust. It threatens us all.”

This story was developed as part of the Catalyst Journalism Project at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. Catalyst brings together investigative reporting and solutions journalism to spark action and response to Oregon’s most perplexing issues. To learn more visit Journalism.UOregon.edu/Catalyst or follow the project on Twitter @UO_catalyst.