Benjamin Gorman, a poet and high school English teacher living in Independence, Oregon, points to the immediacy of poetry as its source of strength. Detailing the process of collaborating over Zoom with Eugene artist Kathleen Caprario for the piece “Patterns of Privilege: Now Hear This,” he recalls a line about poetry’s power that holds a permanent place in his mind.

“It’s from a conversation with Kim Stafford. He points to how poetry responds to what is happening as it is happening,” Gorman says of Stafford, Oregon’s former poet laureate, “unlike a novel that takes more time to put out after that initial spark.”

The immediacy and strength of poetry is what pulled Caprario, primarily a visual artist, into collaboration with three Oregon poets — Gorman, Bobbie Calhoun and Carter McKenzie — for her upcoming work, which was funded by an Oregon Arts Commission Career Opportunity Grant. “Patterns of Privilege: Now Hear This” will be shown alongside the work of four other female artists in the exhibit Social Being, opening at Maude Kerns Art Center Jan. 14.

Gorman talks about how Caprario recognized that their poetry and her textiles “can communicate with one another in a way that will be beneficial to the reader of both kinds of texts.”

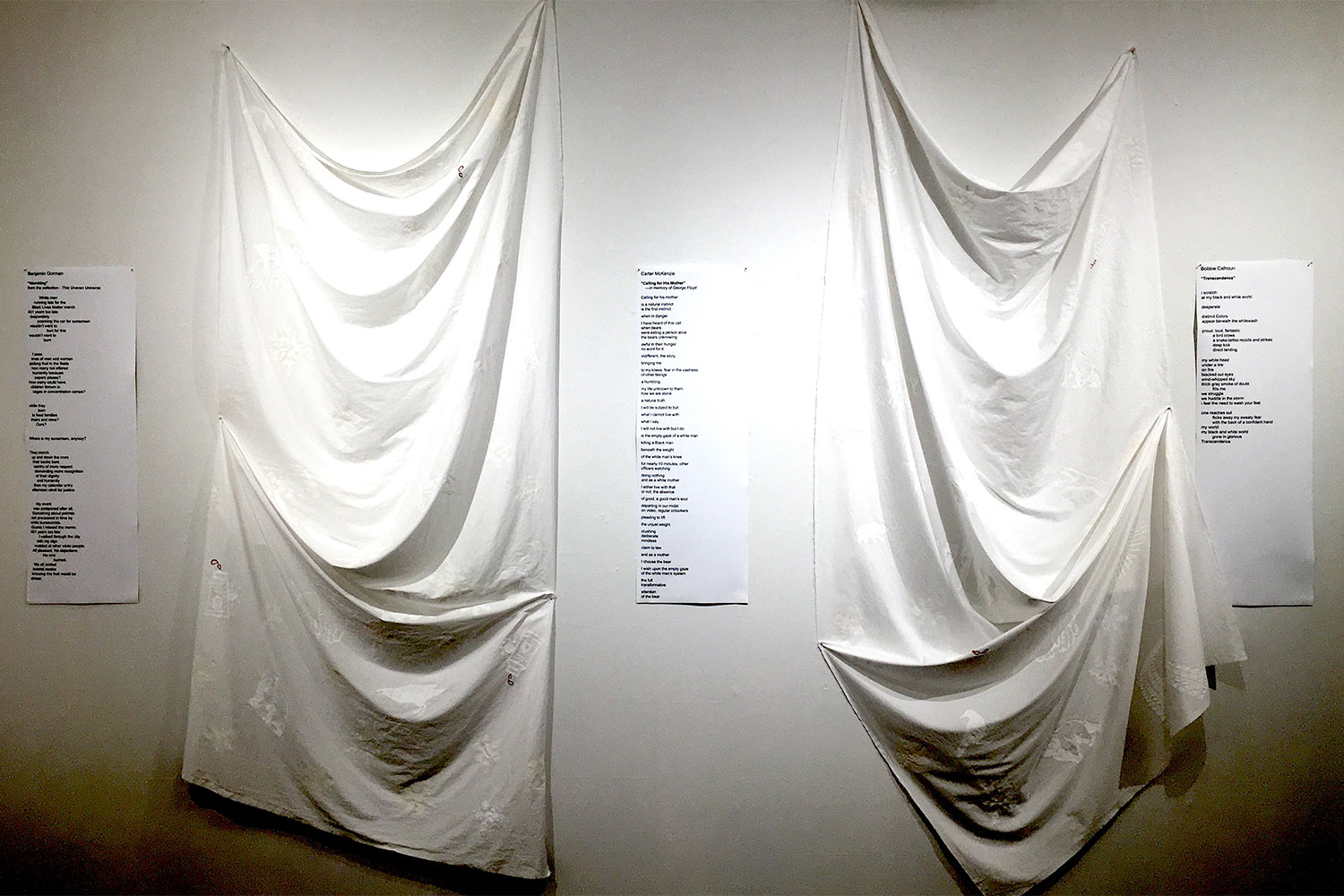

Caprario’s work interrogates her position of privilege as a white woman in an effort to re-examine her own patterns of communication and being without perpetuating what it is she interrogates. “Patterns of Privilege: Now Hear This” displays the printed poems in the sequence Caprario intends them to be read. Between them hang strips of white sheets depicting imagery evoked by the poems.

An adjunct instructor in art at Lane Community College since 1995, Caprario has a well established, yet ever evolving, presence in Eugene’s arts community. After her husband’s death by suicide in 2001, Caprario, who had primarily worked in painting and textiles since her late teens and early 20s, stepped boldly into writing for the screen and dabbled in stand-up comedy. Her short film Mourning After was shown at the Non-Juried Short Film Corner in Cannes, France, in 2014. No matter what the medium, Caprario describes working in layers and making connections.

Caprario notes how in her early years as an artist, any idea that floated into her head felt like fair game. “Now I am much more aware,” she says. Her recent and upcoming work is about social justice. And she points out that it interrogates her position, rather than commenting on an experience she has not had. “That’s what a colonizing culture does, and that is not what I want to do.”

She was inspired by existing work from Gorman, with whom she had worked with before on A Critical Conversation, an exhibit examining the intersections of art, race and privilege, that she produced in conjunction with the nonprofit Eugene Contemporary Art last year.

A Critical Conversation, which was part of Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art’s Black Lives Matter Artist Grant Program Exhibition, reinvigorated Caprario’s belief that “art can — and should — connect with folks on these political and social levels.”

“With A Critical Conversation,” Gorman says, Caprario “wanted it to be clear that the work was about white people’s responsibility.”

The intent and process of this exhibit is driven by this same intention, but Caprario talks about continuing to push her own self reflection in an effort to communicate on a deeper level with her audience. As she was beginning to visualize her process and open up the conversation with Gorman, Calhoun and McKenzie, she asked herself how she could extend the conversation at work with others and with herself.

“It needs to go back in,” Caprario explains of her work. “I need to think about reflection more.”

Self-reflection was the first step, but bringing the poets into the conversation was what really pushed Caprario in this project. “It gave me more insight into what I was trying to do. It encouraged me to keep going,” Caprario says.

An Ongoing Conversation

Calhoun, a poet who lives in Portland and met Caprario through the nonprofit writers organization Willamette Writers, describes how collaborating with her and the other poets has truly been an ongoing conversation.

For this project, “she did not give us any sort of prescribed prompt” Calhoun says of the artist. The freedom Caprario gave the poets to write and revise their own work enhanced the project’s ability to communicate with an audience.

Calhoun talks about how, throughout the collaboration, Caprario emphasized wanting audience members to be able to place themselves within the work. Facilitating a conversational process between the artist and the poets, rather than an agenda for the project, was vital to that.

“All four of us kind of approach the topic differently. There’s value in that.”

Calhoun knew of Caprario’s work and the abstract beauty she is able to produce in her visual art. “I trusted her to find that voice that would speak to her art. And then in turn to create new art out of what the three of us produced,” Calhoun says.

This is the first exhibit that Calhoun and Caprario have collaborated on together, while McKenzie and Gorman were both a part of A Critical Conversation. Each poet points to the conversational form of this collaboration as a catalyst for their writing — and for their re-writing. With the existing work the poets brought to the project, they dove back into and pushed it to a new level.

“It’s really exciting to see your work reflected in another artist’s work,” Gorman says. “And I felt confident knowing her sensitivity and how she works with care on the subject.”

Caprario describes being moved by images in each of the writer’s poems. “Every word in the poem — if it’s a good poem — every single word and how it’s phrased is essential. There’s no waste,” Caprario says. The words which resonated most with her she rendered into physical representations on her textiles.

“From Bobbie’s there’s an image of hands reaching out, and birds and tire tracks. For Ben’s there’s sunscreen, the people protesting and the farm workers. And Carter’s is the bears. The poem that I can’t get out of my mind by her references bears. It’s so strong,” Caprario says.

Caprario first met McKenzie through Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), a national organization with the goal of bringing white people into the fight for racial justice. The poem Caprario is referring to is titled “Calling for his Mother — in Memory of George Floyd.”

Collaborating with Caprario shifted McKenzie’s perspective in the poem. It brought a greater awareness of her own responsibility as a white person.

“When I started the poem, it came out of feeling a sense of outrage and horror. I was really focused on the revulsion at the officer, Derek Chauvin, who murdered George Floyd,” McKenzie says.

But as she began talking with Caprario, she shifted to looking closer at her own place in society and her own biases.

“What happened when I was revising was the need to admit the ways that I’ve been part of this,” McKenzie says.

McKenzie describes the ways she had previously tuned out systemic racism as damaging to everyone. “Because white supremacy dehumanizes everyone. It affects white people differently — they have to do something to tune it out. To tune out the truth of who’s suffering.”

“I had been treating each shooting and each injustice as an individual horror. Not as part of a system, so I could just go back to my life, like it had nothing to do with it,” McKenzie says. “As long as well-meaning white people think that racism has nothing to do with them, racism will persist.”

An Instrument for Change

McKenzie talks about dismantling the idea that poetry and art should be separate from politics.

“Poems ask questions. They engage people so that their emotions and memories are involved.” McKenzie points to this kind of engagement as vital to communicating with an audience.

As she looks ahead to the opening of Social Being, Caprario says she looks forward to seeing how this is received. She is eager to see how audience members identify with the work.

“Does it move people, can they place themselves within the context of the work?” Caprario asks. “And what does that do for their understanding and how they perceive themselves within their community?”

Caprario describes art’s, particularly collaborative art’s, function as a bridge between individual and structural change.

“Beauty can be a real instrument for change,” she says. “And then you’ve got to have structural [change].”

Creating work from where they, as white individuals, are located was vital for both artist and writers in conveying white responsibility in this piece.

“It’s not Black people’s job to show us how to right wrongs,” Caprario says. “This is a white problem. It involves you, but it is more than you. And it’s not right.”

Caprario, McKenzie and Gorman will engage in a Zoom discussion a week after Social Being’s opening. McKenzie says they will talk about the role of art in communicating on social and political issues, and will be happy to answer questions about the poems and the collaboration process for this piece.

Then the first Thursday of February, Caprario and the four other artists who have work in Social Being — Sandra Honda, Mei-ling Lee, Charly Swing and Kerry Weeks — will host a Zoom discussion where they will dive into the rich conversations that emerge from the socially engaged art.

“I want this to be an ongoing conversation,” Caprario says. “The work doesn’t stop here.”

Social Being will be at Maude Kerns Art Center, 1910 E. 15h Avenue, from Friday, Jan. 14, until Friday, Feb. 11. Suggested donation of $3/person, $5/family. Zoom discussions will be held 6-7 pm Thursday, Jan. 20, and Thursday, Feb. 3. More information on gallery hours and registration for zoom discussions at MKArtCenter.org.