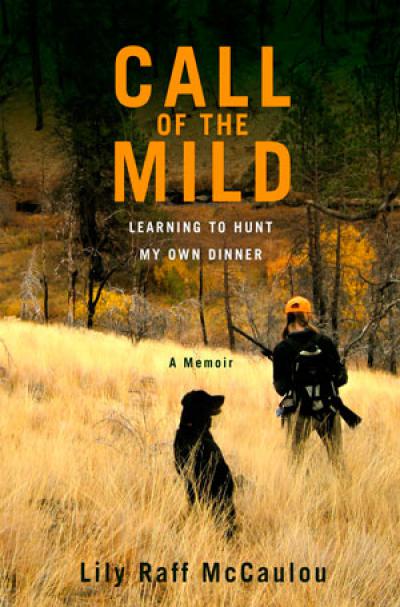

(OR.) CALL OF THE MILD: Learning to Hunt My Own Dinner By Lily Raff McCaulou. Grand Central, $24.99.

MEAT EATER: Adventures from the Life of an American Hunter By Steven Rinella. Spiegal and Grau, $26.

The image many non-hunters have of hunters isn’t pretty. Hunters are callous, camo-clad rednecks in big trucks, gun-nuts unconcerned about their prey and the environment in general. There are boorish hunters to be sure. But let’s not forget, Steven Rinella (American Buffalo, The Scavenger’s Guide to Haute Cuisine) tells us, that America’s first conservationists were avid hunters. And — as Lily Raff McCaulou finds to her own amazement — becoming a hunter might make one a better environmentalist. Digging deeper, both agree that hunting has something to tell us about who we are and how we fit in with the world around us.

McCaulou, raised by uber-hippie parents in suburban Maryland, a stone’s throw from Washington, D.C., is the epitome of the clueless urbanite when she ditches the glamour of the New York film industry to take a newspaper job in Bend in 2003. Assigned a rural beat, McCaulou stumbles onto a discovery: Hunters know an awful lot about the places they hunt. What’s more, the hunters she meets evince a profound love for the animals they pursue and nature in general.

Soon, McCaulou herself is hunting, in order to build a connection to the Oregon country she’s learning to love and, more importantly, to the food on her plate. Hunting proves no small challenge for a woman who doesn’t know the front end of a deer track from the back, and who is so afraid of guns that she frets in Call of the Mild over even touching an unloaded rifle.

McCaulou doesn’t just struggle with her fear of firearms. What kind of relationship does she want with nature? Does she have what it takes to kill her own dinner? Finding out becomes gut wrenching when McCaulou faces a wave of deaths among her friends and family and draws connections between the lost lives of her loved ones and the wild animals she targets. Ultimately, she decides the connection hunting gives her to the food she eats and the place she lives — a connection missing in the prepackaged meat on grocery store shelves — is vitally important: “If humans stop hunting, we could lose some of our humanity.”

Rinella is McCaulou’s polar opposite: born into rural Michigan’s hunting culture, a former professional trapper, author of two previous hunting books and host of two hunting-related cable TV shows. Though aware of the disdain that urban, agriculturally dependent society feels for hunters, Rinella doesn’t need to discover that hunting is part of the primal human identity — that’s where he starts out. He sees hunting, and writing about it, as “an act of guerrilla warfare against the inevitable advance of time,” probing what it means to be a hunter in 11 episodes from a lifetime spent in the field. Most include “Tasting Notes” on an impressive variety of game, from squirrel and venison to beaver tail and cougar.

Where McCaulou’s memoir is geared towards non-hunting readers — maybe to explain why a perfectly sensible liberal woman might embrace camouflage and pick up a gun — Rinella’s is fully grounded in the genre of hunting stories, gritty and primal, perhaps exhaustively so to the non-initiated.

If you didn’t guess from reading the title, Meat Eater, Rinella is unapologetically enthusiastic about turning animals into food. He doesn’t shy away from the bloody underbelly of hunting, pondering the exhilaration of the kill, the metaphysics of the “right way” to kill and reconciling the hunter’s “happiness over an animal’s death with your sense of reverence for its life.” By justifying the role of hunter in a modern world, he’s arguing for protecting the remaining wildness in human nature against the creeping encroachment of civilization. While his philosophies might ring true for those comfortable with eating meat, they could be tougher to swallow for the animal rights crowd.