Life is sweet, mostly

Gabrielle Hamilton’s Blood, Bones & Butter a nourishing, satisfying memoir

By Vanessa Salvia

|

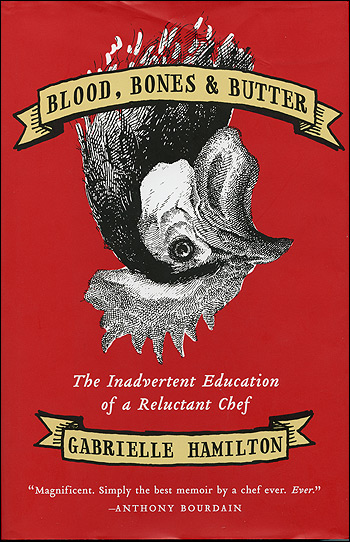

Chef and restaurant owner Gabrielle Hamilton never intended to be a chef, or a restaurant owner. That much we get from the title of her memoir, Blood, Bones & Butter: The Inadvertent Education of a Reluctant Chef. She never attended culinary school ” her finest education was as a child watching her French mother put her collection of burnt orange LeCreuset cookware to use, feeding her family of seven with “dark, briny, wrinkled olives” and small birds the kids “would have liked as pets.”

But after a lifetime of restaurant work, starting with the dishwashing job she lied her way into at age 13, it’s not surprising that she became proprietor of a small but immensely popular restaurant, Prune (her grandmother’s nickname for her), in New York’s East Village. What is more surprising is how easily Hamilton created a book about a life completely intertwined with food that is really more about family, and nowhere near as trite as the typical food memoir.

Hamilton is a nose-to-tail chef, and is equally raw and revealing with her use of words. Her metaphors are rich with meaning and emotion; the book is filled with perfect sips of words that you sometimes just want to read over and over again, yet her memoir doesn’t contain recipes and she doesn’t dwell on overly vivid descriptions of food. Some of her passages, about her own mother in particular, are so angry and painful they’re difficult to digest.

Hamilton blossoms from a contented youngster nestled in the embrace of an eccentric but tight family into a teenage hoodlum who “grazed through the menu of adult behavior.” She married an “Italian Italian” man who wooed her with fresh hand-made ravioli, with herbs and ricotta visible through the thinly rolled dough “like a woman behind a shower curtain,” despite the fact that she was already in a long-term relationship with a woman.

At first, her green-card marriage is nothing more than “performance art,” yet after two sons and seven years (and the chance to cook with her husband’s old-world mother), she longs for it to be something more. Though she finds that her years as a chef more than prepare her for the challenges of motherhood (changing a diaper is just like trussing a chicken), Hamilton’s happiness never solidifies the way she hopes it will ” around each turn of her life, what little glitter there was continually fades, and Hamilton seems to stretch herself thinner and thinner, like that pasta dough, looking for a way to retrieve the hope and promise she felt as a child in rural Pennsylvania in the ’70s. She sometimes seems to purposely trudge down the hardest road while eagerly giving the finger to anyone in her way, yet there’s a resiliency within her we come to admire.

Hamilton’s success at Prune, and in her writing life, was seemingly borne from the most difficult struggles. And yet, what she created with this book is nourishing and satisfying. Perhaps that is a living testament to her artist father, from whom she learned, long ago, “how to create beauty where none exists, how to be generous beyond our means, how to change a small corner of the world just by making a little dinner for a few friends.”