People for Sale

Sex trafficking hits home in Lane County

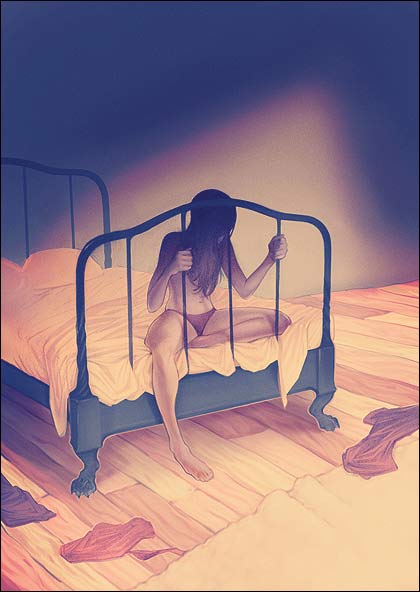

Words by Shannon Finnell | Illustration by Sam Wolfe Connelly

|

In sleepy little Eugene, some 90 miles south of the maligned “Pornland” and far from the populous cities of San Francisco and L.A., there would seem to be nothing for sex traffickers to prey on: no destitute starlets, no major international port, no out-of-control crime wave to hide behind. But local treatment facilities, women’s advocates and law enforcement say Eugene is no stranger to sex trafficking, and it’s not just that trafficking passes through rural Oregon on I-5. Lane County is a recruitment ground and a market for sex traffickers.

“Most of the chronically homeless youth that we see have come against it — they’ve been solicited to be involved or have been involved,” says Liz Schwarz, director of homeless and runaway youth services at Looking Glass Youth & Family Services. Schwarz says that the vulnerability of homeless youth makes them ideal targets for pimps or gang members who traffic people for sex.

The city of Eugene reported that in 2008-2009, Looking Glass served 1,945 runaway or homeless youth. Schwarz estimates that they’re now seeing about 150 chronically homeless youth (“a super ballpark figure,” she says), and she isn’t sure about the solicitation rate of youth that are homeless but not classified as chronically so.

Organizations such as the Zonta Club of Eugene, which advocates for the condition of women and girls worldwide, try to bring local attention to sex trafficking issues. Zontian Liz Ness says that a lot of people don’t even understand what trafficking is. “The definition of trafficking is NOT moving a person,” she says. “You don’t have to move a person to traffic. It’s having someone do something they really aren’t wanting to do.”

That extends to forced labor, which is estimated to be the largest component of human trafficking, and sexual exploitation through physical force, threats of violence or manipulated drug addiction. Sex trafficking also includes situations in which people who are trafficked are promised money in exchange for performing sex acts and never receive it.

Lane County District Attorney Alex Gardner says that some traffickers make it a priority to take a victim’s cell phone, download the numbers and memorize other personal information. Then the traffickers taunt and physically threaten not only their victims, but their victims’ families and friends. Gardner gives the example: “They say, ‘I’ll rape your little brother.’”

Ness says that even when compared to survivors of other abuses or mental illness that are often difficult to acknowledge, people who have been trafficked for sex have a tough time coming forward. “It’s so hard to get a trafficking victim to speak. You can have someone be abused, raped, drug addicted, and the difference with trafficking is that these girls feel such overwhelming shame — which is so sad because it’s not their fault.”

While those being trafficked are trapped in a world of abuse and survival, Ness says that traffickers tend to have violent but businesslike mindsets about sex trafficking. “It’s the one thing in which you have a renewable resource,” Ness says, “and the biggest market is for underage girls.”

“We’ve got to stop tolerating sex trafficking and treating it as if it’s just a victimless crime, because it’s not,” says U.S. Attorney Dwight Holton. “The Pretty Woman image is not the real world, in my experience.”

According to Holton and Assistant U.S. Attorney Kemp Strickland, they prosecuted a case in June that contains elements more typical of the real world:

A.K., a troubled 14-year-old girl, was targeted by 36-year-old James A. Jackson in Seattle. Ideal prey because of her problems, she was soon groomed by Jackson for forced prostitution. He brought her to Portland, where he beat her, choked her and forced her to have sex for money.

Jackson tried to make her easier to control by addicting her to cocaine, forcing her to use and telling her about his abuse of the last girl who refused, but A.K. told the court that addiction never really took. She still has a physical scar from an instance when Jackson tried to bite off her finger. Eventually, when A.K. was certain Jackson was about to kill her, she promised to cooperate and earn $20,000 for him if he allowed her to live.

Dear Johns

Three new pieces of legislation passed this year in the Oregon Legislature will change the consequences of engaging in human trafficking in Oregon, Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Floyd Prozanski told EW. It’s part of a growing focus on the roles of traffickers and “johns” in the sex trade.

House Bill 2714B creates the crime of patronizing a prostitute. It might seem like paying for sex has long been illegal in Oregon, and it has. But until now, the prostitution statute treated the prostitute and john as equals, even as the balance of power swung in the john’s favor. The new crime is a Class A misdemeanor with a mandatory first-offense fine of $10,000.

The House bill also takes away the johns’ defense of not knowing the age of underage prostitutes. That’s more consistent with Oregon’s statutory rape laws, which state that no defense exists for defendants who claim age ignorance of a child under 16, and place the burden of proof of belief on the defense when the minor in question is 16 or older (ORS 163.325).

Similarly, Senate Bill 425 removes the requirement that the prosecution prove that a person charged with compelling prostitution of a minor be aware of the minor’s age. It adds “aids or facilitates” to the definition of the crime of compelling prostitution, which already included the words “compel,” “induce” and “cause.” “It makes it clearer for law enforcement looking at facts present in a given case if a person has in fact committed the crime,” Prozanski says.

Traffickers’ assets can now be confiscated, because Senate Bill 430 makes human trafficking subject to civil forfeiture. Mostly a consequence of drug-related offenses, civil forfeiture will allow police to seize items purchased with the proceeds of human trafficking and items used to traffic people, such as cars, houses and computers, and give those proceeds to Court-Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) volunteer programs.

In addition to helping fund those programs, Prozanski hopes the likely loss of financial benefits from trafficking will make the crime a less appealing get-rich-quick scheme. “We believe the pimp or individual who is coercing the young woman into these acts will see a likelihood of losing items of value,” he says.

In June, Sen. Ron Wyden wrote a provision for the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2011, which Congress will consider later this year. The provision would give block grants to regions with significant sex trafficking activity, and the grants would be used for basic needs, counseling and education for child victims, as well as community outreach and training for law enforcement.

Enforcement

Cases of sex trafficking are prosecuted both locally and federally. Different factors, such as interstate travel, a defendant’s criminal history and the involvement of interstate commerce affect the jurisdiction.

Local investigations, though, are generally where court cases originate. Lane County District Attorney Alex Gardner says that sex trafficking is intertwined with drugs and the gangs peddling both drugs and people. He says there are hundreds of gang members in Lane County, and some make a lot of money trafficking people for sex.

“When our drug investigation teams were strong, we had a robust system of informants who also shared information that helped us find trafficking victims, because the need for drugs put all of the people involved together, at least intermittently,” Gardner says in an email to EW.

Gardner says detectives learned a lot from those informants. Gang members recruit young local women into nude dancing, and eventually that changes to prostitution.

“The gang members were extremely sophisticated in terms of the techniques they used to profile/identify vulnerable women,” Gardner says, describing a local case that exhibited the earning power and organization of gangs that traffic. “Once the young women were identified, the techniques used to recruit and retain them were similarly sophisticated. The gang members started with charm and generosity and moved quickly to threats, brutality and isolation.”

Just as 14-year-old A.K. was taken from Seattle to Portland, in order to make the situation feel inescapable, Gardner says, most of the local girls and women are taken to unfamiliar areas in Washington, Nevada or California, where their abusive relationships with traffickers are also their lifelines. Schwarz says it’s similar to the domestic violence cycle, where the trafficker is an abuser and simultaneously a protector or provider.

Strickland says that although I-5 is a major thoroughfare for sex trafficking, there are many connected corridors across the country. Seattle, Sacramento and Las Vegas are major hubs, so everything on routes connecting them can be used for trafficking and recruitment.

The Lane County Sheriff’s Office recorded 28 prostitution arrests in 2009, which makes the number of trafficking cases — whatever the proportion — look low. But Looking Glass, the Zonta Club and Gardner say that cops try to remove trafficking victims from dangerous situations and find help for minors involved in prostitution while also pursuing traffickers. They want to prosecute traffickers whenever possible, but not at a cost to the victim. This makes the number of prostitution arrests a poor indicator of sex trafficking. Also in 2009, EPD rescued seven underage girls from sex trafficking.

“The fact is that metrics on this are hard to come by,” says U.S. Attorney Holton. “It’s hard to get accurate data on this.” From his experience in the Justice Department and what he hears from law enforcement, Holton says that based solely on his observations, the rate of sex trafficking is, in fact, rising.

Gardner says that the county is doing what it can to investigate human trafficking, but Lane County is down to 14 patrol deputies and four detectives for 4,600 square miles of land. The Eugene Police Department has three detectives and one sergeant in the Vice Narcotics Unit, investigating both vice and drug cases.

“I suspect what we need most is additional resources to investigate the cases and protect and care for the victims,” Gardner says. “I know Senator Wyden cares about this issue and is working on it, but the federal budget is in terrible shape, as you know, so it’s unclear whether any legislation will provide the resources we need to make a significant dent in the problem.”

Holton echoes the need for more resources for law enforcement, but says that prevention and treatment are important, too. “The preventative efforts on the front end — that’s how we’re going to end this problem,” Holton says.

No Funds

Ness and Looking Glass CEO Craig Opperman say that Looking Glass’s Station 7 is the only Eugene facility they’re aware of that has specialized care to address the needs of minors who have been trafficked for sex. Looking Glass also has facilities that work with young adults.

Opperman says that while Looking Glass has many different funding sources, their money comes mostly from federal grants and the Lane County Human Services Commission. But as revenues to the federal and county government dwindle or dry up, that loss is passed on to local community services like Looking Glass, which now faces close to a 30 percent reduction in funding.

“We’ve got shelter spaces and trained staff that can really help to work with kids on letting them know they could and should find a way out and testify,” Opperman says. “But we don’t want to tell them that if we can’t follow through.”

Part of persuading sex trafficking victims that leaving their traffickers is a good idea is giving them alternative ways to meet basic needs like shelter and food, and also showing them that it’s safe to leave their traffickers. Looking Glass tries to provide these needs as well as offer safety, but it costs Looking Glass money that is getting harder to come by.

Opperman says, “There can be people waiting to get in but we don’t have the resources available. If someone comes to you three or four times and you don’t have spaces available, they can stop coming.”

Schwarz says that when people who have been trafficked for sex come to Looking Glass, the first priority is to immediately meet their basic needs and start building trust. After this, the goal is to introduce more support services, case management and counseling services. “It takes so long to build trust with that population because of the trauma that’s involved,” she says.

Schwarz says it’s difficult to keep track of statistics and emotional progress, because after their basic needs are met victims often leave town to ensure their own safety.

Just as laws have been changing to address those selling sex as likely victims, Schwarz says Looking Glass is starting to work with EPD to bring underage sex workers to its facility instead of lockup whenever possible.

She says that even though financial resources are tight across the board, funding help for sex-trafficked people under 18 is slightly easier than funding it for those who are legally adults. That’s a problem, Schwarz says, because sometimes people first trafficked in their early or mid teens don’t seek help until they are discovered by law enforcement or begin to believe, against the odds, that there might be a way out — at which point they’re too old to be considered child victims of trafficking.

“The ones that we’re able to ID well are the young adults,” in the 16 to 22 year-old age range, Schwarz says. “The 18 year olds we see started when they were 15 or 16.”

Young adults who have been sex trafficked often face a greater stigma, Schwarz says, because there’s some sense that they must have been complicit in their trafficking. “Society is much more likely to think of them as a prostitute,” she says. “Society definitely looks at that differently, and their situations aren’t necessarily that different.”

A.K. was eventually arrested for prostitution in Portland, when she was still 15, and she agreed to testify in exchange for help from the police. In the interim, Jackson had made about $45,000 by trafficking A.K. He didn’t allow her to keep any of the money, and he continued to beat her approximately three times a week, according to documents.

She moved to a safe house outside of Oregon and testified against Jackson, who received a 40-year prison sentence in June, three years after A.K. was discovered but only a short time after she became a legal adult.

Jackson’s record for assault on women goes back to 1992 — the year before his victim was born. Before his conviction for trafficking A.K., he’d been convicted of 26 crimes, including harassment, attempted unlawful imprisonment and multiple assaults against women. Although there’s no evidence he was trafficking the women he was convicted of assaulting, sometimes police do arrive at a situation that looks like domestic violence and later discover sex trafficking.

Schwarz says that despite media coverage discussing how trafficking works, people don’t realize that the crisis is local and constant. “It’s here, it’s happening here,” she says. “You see a lot of very sensationalized stories about sex trafficking, but there’s every day trafficking, and all youth are vulnerable.”