MOVIE REVIEW ARCHIVE | THEATER INFO |

Who Owns Culture?

Power plays for art in and around Philly

by Suzi Steffen

THE ART OF THE STEAL: Directed by Don Argott. Producer, Sheena R. Joyce. Cinematography, Dan Argott. Editor, Demian Fenton. Music, West Dylan Thordson. IFC Films/Sundane Selects, 2009. Not rated. 101 minutes. ![]()

|

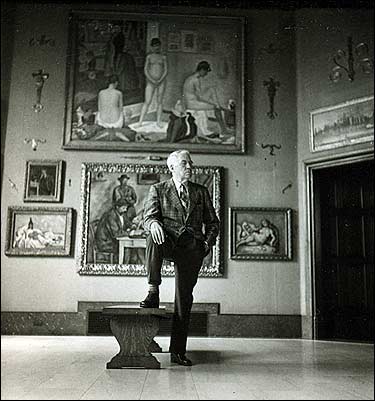

| Dr. Albert C. Barnes in his home, the Barnes Foundation |

The Art of the Steal provides enough intrigue to stock a few other movies, ones I’d expect to be fiction. The documentary’s replete with twists and turns of powerful, greedy elites planning cultural life for “the public good.” It’s stuffed with back-room political deals and shenanigans that give a corporation charitable status and pit art lovers against the city’s art museum and newspaper — and it illustrates the ways a cash-strapped historically black college was railroaded by a white governor and his cronies, including the state’s attorney general.

Along the way, the Annenberg Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trust, the city of Philadelphia and an arts reporter at the Inquirer take more than a few hits, some at the hands of civil rights leader and NAACP chair Julian Bond.

Filmmaker Don Argott says he knew nothing about The Barnes Foundation when he began working on the documentary, which was funded by a former student at the foundation. Named for Dr. Albert C. Barnes, a working-class-boy-made-good who was snubbed by and thus loathed the cultural elites of Philadelphia, the private collection contains what its advocates keep referring to as “the best Post-Impressionist collection in the world.” Certainly, it’s got the most Renoirs (though just as certainly, those late Renoirs are less than his best), but there are enough Cézannes, Matisses and other important art from Europe, Africa and Asia to make the Barnes Foundation an unrivalled treasure trove.

That trove, which Barnes wanted to remain as he set it up in the buildings on his grounds, for the good of the students at his foundation (whose philosophical leanings one might consider a bit eccentric), landed smack-dab in a cultural tug-of-war as soon as Barnes and his main follower both died. Barnes didn’t want the Philadelphia Art Museum or anyone associated with newspaperman Walter Annenberg to get their hands on his collection, and he left clear directives about how to handle the art. That has all been ignored, to put it mildly.

Argott couldn’t get current Barnes Foundation board members or the head of the Pew Charitable Trusts, who takes a lot of abuse in this movie, on camera, but former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell basically admits that he made some deals and put pressure on people to help get Barnes’ art away from Barnes’ property and into downtown Philly.

The film presents this as a tragedy, and those who believed in Barnes’ particular and specific legacy no doubt see it that way. But who truly owns cultural legacies like the Barnes Foundation? Will more people see the art on the Parkway than would have seen it in Lower Merion, where visiting hours were limited and neighbors disliked the traffic? Of course, that outcome doesn’t make the unsavory details any easier to swallow or the charitable foundations any shinier (Pew’s response is online at http://wkly.ws/h0; Julian Bond and others respond to a Washington Post critique of the film at http://wkly.ws/h1), but some honest discussion about access and what the public good means could have balanced the film. Still, it’s a reminder that arts journalists (including me) should do a lot more to follow the money instead of uncritically accepting the word of large cultural institutions — and it’s a fascinating, horrifying look at how one man’s legacy and intention were attacked and dismantled by a tourist-dollar-chasing governmental, business and nonprofit “cultural elite” gang behaving like thugs.