I’m a shy dater, and a picky one. At least those are the excuses I like to wield for my lack of romantic history — who knows, I guess I could just be horribly uninteresting and un-date-able, but let’s go with my personal affliction of being a shy, picky dater.

The fact that I’m a black, mixed-race woman in Oregon doesn’t help.

Sure, I was interested in boys growing up, but the boys I crushed on always seemed to date girls who were virtual opposites of me: white, thin, with straight, silky hair.

I gave up, for the most part, until about halfway through college. Then I tried Tinder, the phone dating app where you swipe (right for yes, left for no) on online singles in the area, but I found my shyness and uncertainty allowed me to only swipe right on my friends and joke about the absurdity of looking for love or meaningless flings on the popular app.

At that time, about three years ago, I talked with one of my good friends, also a black woman, about her experiences with online dating. Unlike myself, she was using Tinder and OkCupid in an actually serious manner but, instead of love, she was finding a whole bunch of casual racism.

Dasha Snow, 22, still uses Tinder occasionally, though she recently retired her OkCupid. At the time we first talked about her qualms with online dating, she lived in Eugene. Now she resides in Portland, but says not much has changed.

When I ask her if she’s had a mostly negative or mostly positive experience with online dating throughout the years, she says: “By far, majority negative.”

Snow says that when she was more active on dating apps, she would receive messages addressing her race every day or every other day. “It was extremely common,” she says.

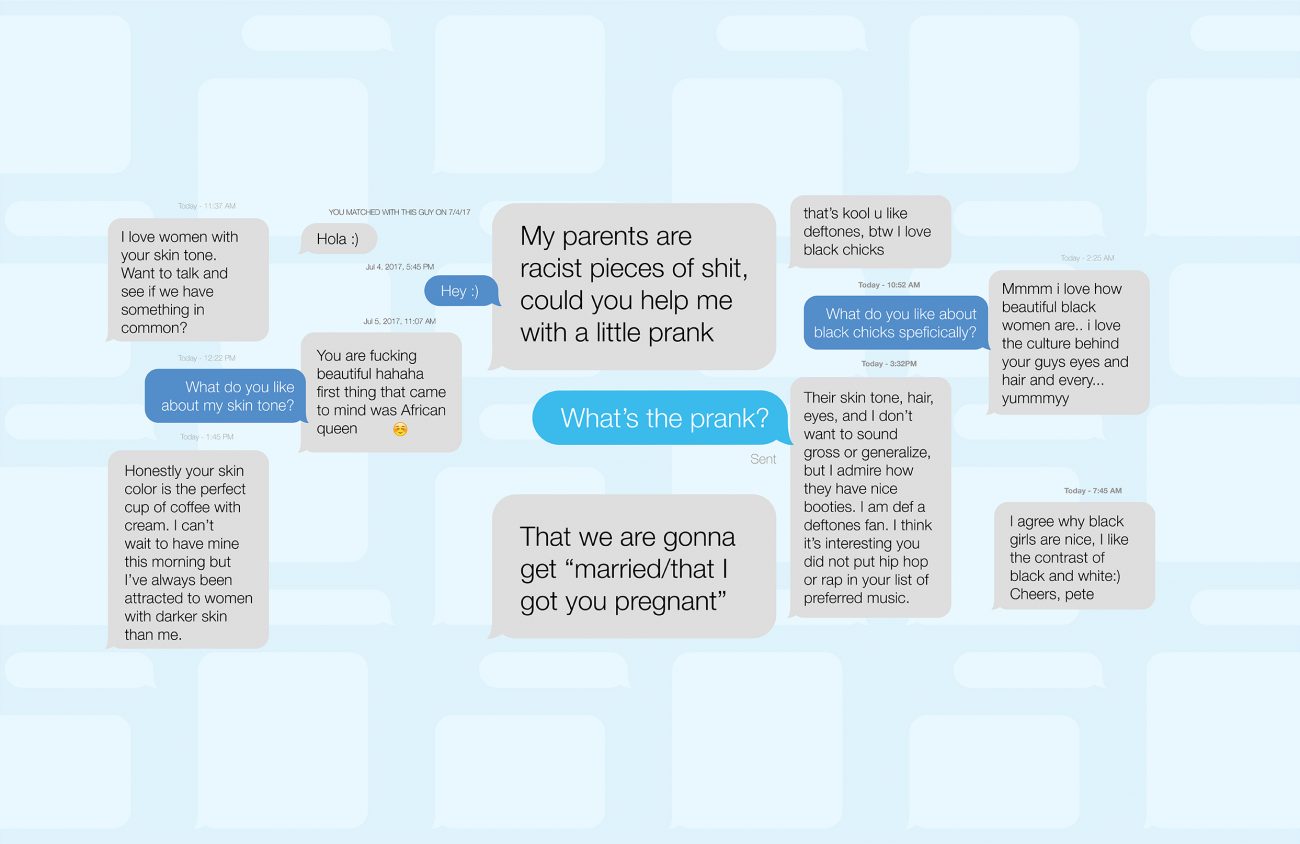

The messages she’s received have spanned from fetishizing her race, making stereotypical remarks or even to claims by people who say they matched with her “on accident” since they don’t like black women.

One example of a message she received was from a man on OkCupid who said he loved “black chicks” because of “their skin tone, hair, eyes, and I don’t want to sound gross or generalize, but I admire how they have nice booties.” He continued by telling Snow: “I think it’s interesting you did not put hip hop or rap in your list of preferred music.”

Although I’m now in a serious relationship, for this story I decided that I would give Tinder another try, and also sign up for OkCupid, to see what kind of reactions I got from the Eugene area. I also had assistance from my white coworker, who acted as a control for the experiment by making a nearly identical Tinder profile to determine the difference in responses we got.

We created our Tinder profiles to state the same information: first name, age, journalist, Eugene. We picked similar photos — selfies, a nicer headshot and pictures with our respective pets.

From there, the rules were simple. We set our accounts to view men only, kept the generic 18-32 year-old age range the app gave us, set a 100-mile radius and right-swiped every person that came up. Tinder limits you to 100 right-swipes, or “likes,” every 12-hours, so that kept us at the same number of swipes for comparison. We would only respond “Hey!” one time if they engaged us first in a message.

We did this for two weeks.

Seeing as my friend Snow had been dating online for about three years, I wasn’t expecting to receive any responses equitable to hers in only two weeks — but I did.

My coworker and I got a comparable amount of greetings, funny pickup lines and sexual requests, but the biggest standout was that the ones I received mentioned my race, while hers did not.

From icebreakers that involved my race — like the Tinder user who asked me if I wanted to help pull a prank on his “racist pieces of shit” parents in which he would tell them that he got me pregnant and we were going to get married — to people who have clearly never interacted with a black person before — like another Tinder user who said my hair reminded him of Hey Arnold! — to gross racial fetishization.

One message I received on OkCupid read: “I love women with your skin tone. Want to talk and see if we have something in common?” I asked him what he meant by that, to which he responded, “Honestly your skin color is the perfect cup of coffee with cream. I can’t wait to have mine this morning …”

Snow says being compared to food items is a normal occurrence.

“On OkCupid, anyone can message you — you don’t have to match with them or anything — so I’ll just get random messages from random people and they’ll just be like, ‘my chocolate mami’ or something, or ‘I really like your skin tone, very unique and delicious,’” Snow says.

Along with the fetishization, on the other end of the spectrum, Snow says she often gets outright ignored while online dating.

In the two weeks of our experiment, my coworker procured 906 matches — or men who also “liked” her — while I ended up with 787.

The 119 less matches I received correlated with Snow’s feelings of being ignored, as well as with a study OkCupid put out in 2009, and updated in 2014, which revealed that black women tend to encounter the cold shoulder when looking for love online.

OkCupid’s 2009 report showed that although black women respond the most to messages sent to them (“In many cases, their response rate is one and a half times the average, and overall, black women reply about a quarter more often than other women”), they receive the least responses when they’re the ones to initiate the conversation. They’re responded to an average of 34.3 percent of the time, versus an average of 42 percent for women as a whole.

The site also has a feature similar to Tinder in which users swipe profiles right if they’re interested and left if they’re not. In its 2014 report, OkCupid released data from such a swiping system that showed Asian men were 20 percent less likely to swipe right on a black woman, Latino men were 18 percent less likely, white men 17 percent less likely and black men only 1 percent more likely to swipe right on a black woman than any other race.

“82 percent of non-black men on OkCupid show some bias against black women,” the study says.

This data was specifically for heterosexual users, but OKCupid’s 2014 study also displayed data for users searching out same-sex relationships, and the data was similar for black women there.

Snow has looked for both men and women on dating apps, and says women tend not to show interest in her.

“It’s hard to pinpoint, because maybe they just don’t find me attractive, but it’s been really hard to find women to date here, too, and it’s hard to not think that race has something to do with it,” she says.

This type of treatment is not limited to women. Men of color and gender non-binary people of color also face racism when looking for love online.

Kainoa Pilai is a 24-year-old gender non-binary trans person who uses they/them pronouns. They’ve been using dating apps for about six years.

They say their staple app has been Grindr, roughly the equivalent app to Tinder for gay, bi, trans and queer people. “It’s pretty much geared for anyone who’s not straight,” Pilai says.

Pilai is now in a non-monogamous relationship with their current partner, and is still using Grindr “every now and then.” When they used the app more frequently, they say, racist messages were a regular occurrence.

“At least weekly I’d run into racist nonsense, be it on the fetishization end or on the more violent, antagonizing end.”

They continue: “I’ll either have people just flat-out tell me, ‘I don’t like black people’ or, like, ‘Sorry you’re not my type,’ which most of the time is code for the same thing — especially in Oregon.”

Grindr is especially infamous for some of its users’ very blunt racial preferences. Pilai says they regularly stumble across profiles that include statements like: “No [insert race here].”

“I just don’t message them, obviously,” they say of the racially discriminatory profiles. “But, I’ll keep my eye on them,” Pilai adds. “These aren’t just cute preferences; this is actively harmful shit.”

Living in an area that touts itself as being progressive and accepting of diversity, this ignorance towards race in the realm of online dating is especially disappointing.

“Specifically here it’s like, honestly at this point it’s defeating. It just feels like a blow after blow after blow of people telling you that you’re not good enough just because you’re not white,” Pilai says. “That’s honestly what it boils down to when people tell you these coded messages that boil down to, ‘Don’t talk to me if you’re black.’”

Although people with racist tendencies on online dating sites may seem like a niche category of the nation’s population, this isn’t just about a problem finding a date. The racism faced online by people of color is a microcosm of larger issues of beauty and worthiness in our society.

“It’s really important for people to acknowledge that these dating preferences are rooted in what’s called Eurocentric beauty standards which are a widespread, arbitrary set of beauty standards projected by media that we consume,” Pilai says, “and it shows that whiteness is most beautiful and white features are beautiful.”

Think about the models we regularly see on billboards or America’s A-list celebs — a majority of them, even if they’re not white, have Eurocentric features: slim noses, silky hair. I’m saying majority here, because obviously we have A-listers with darker skin tones and “kinky” natural hair that don’t fit in to this mold, like Lupita Nyong’o.

But you don’t see Hollywood overrun with women who look like Nyong’o. You do, however, see multiple women who look like, say, Nicole Kidman, Scarlett Johansson or Charlize Theron.

These beauty standards come out in dating apps like Tinder, where you make a split-second decision of whether you want to swipe someone right or left based on their photos. But they also come up in the more platonic interactions of our everyday lives when we meet someone for the first time — in job interviews, at work interacting with customers, when trying to rent an apartment or AirBnB.

The way you’re perceived changes the way you’re treated — online or off.

Is this person presentable? Are they professional looking? Are they worth spending my time on? All these questions are subconsciously answered in a split-second based on appearance.

These are all things that are constantly on my mind as someone who is not white.

All I know is: I’m very happy I’m not single.