I killed a buck on Halloween night two years ago.

It was late, almost midnight and I was driving home from a night of watching movies and eating pizza. I’m a notoriously slow driver, so I wasn’t going very fast as I approached a curve on Cloverdale Road south of Eugene.

I never saw the buck before I hit him. I never hit the brakes. He leapt out of a ditch and in front of my Jeep Patriot, and all hell broke loose.

I sat there stunned, as the smoke from the airbags and my smashed engine cleared, before getting out to assess the damage.

The buck was dead. So was my Jeep.

Oil was pooling under the car and trickling toward the muddy ditch where the buck lay sprawled. I called my friend Leslie to come pick me up, then my insurance company and a tow truck.

Leslie looked at the mess and declared me an honorary Republican for a day. I’d killed a deer, caused an oil spill and potentially contaminated a waterway (all of which I pointed out to the nice deputy sheriff who pulled over to ensure no one smashed into us as we waited for a tow).

The next day I got three main questions: “Are you OK?” Followed by: “I’m sure you must feel terrible that you killed that deer,” from my Eugene friends. And: “Did you take him home to butcher and eat him?” from the rural Lane County crowd.

In answer to the first, I was sore and whiplashed and wound up with a couple months of chiropractic. Did I feel bad? A little. I’m an animal lover, but there’s no way I could have avoided hitting him. As for eating the deer, I’m a vegetarian and that precludes me from wanting to eat Bambi, let alone a Bambi soaked in oil and ditch water.

Also, it’s not legal to eat roadkill in Oregon.

Or at least it hasn’t been. But as of Jan. 1, it will be legal to butcher and eat your roadkill deer in the Beaver State, and that’s good to know, because you might have noticed that there’s an awful lot of them careening into the roads right about now.

Before you whip out a knife and start skinning your buck, there are some details you need to be filled in on.

Enlarge

Illustration by Sarah Decker

Who Killed Bambi?

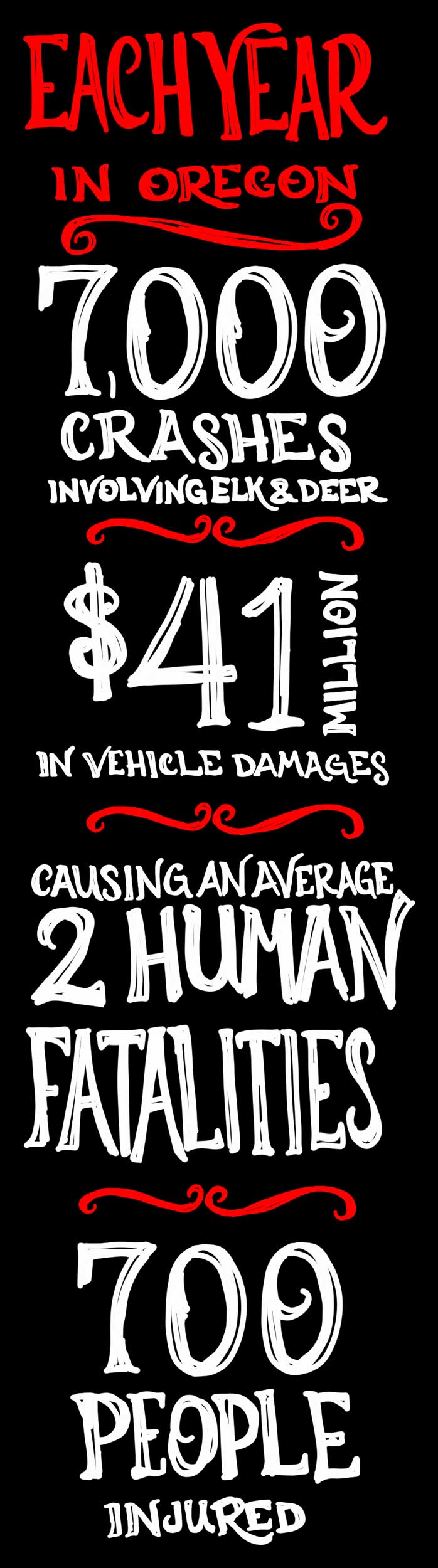

According to the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), statewide there are about 7,000 collisions a year with deer and elk, causing $44 million in damages and injuring more than 700 people. An average of two people die per year in these collisions.

Here in Lane County, according to county spokesperson Devon Ashbridge and Becky Taylor, senior transportation planner, there were 79 reported vehicle-animal collisions.

Ashbridge says most of them were in November and during the early morning, 5 to 7 am, and at twilight after 4:30 pm, in clear and dry conditions. Marcola Road had the most hits with 12, and three other roads had four collisions each: Jasper-Lowell Road, Row River Road in Cottage Grove and 30th Avenue in Eugene.

Taylor says, based on the carcasses removed from county roads, the number of animal strikes is probably 500 times the reported figures. Roadkill is reported to the Department of Motor Vehicles if someone is injured (aside from the animal) or the damage exceeds $2,500.

So the bad news is hitting a deer or elk is bad for you, bad for the animal and bad for your vehicle.

The only good news is now you can eat the deer — if you are up for it after it’s just bounced off your car. If it was an elk, it’s highly doubtful you or your vehicle will be up for butchering and transporting the 700 lb animal after running into it.

So many deer meet your bumper in November for two main reasons. One of them is the time change making the commute darker in the evenings; the other is because the bucks are running around distracted by lust. They are in rut.

Right around the time you are thinking about the holidays and about driving to grandma’s house for Thanksgiving, Bambi and his buddies are thinking about making cute little deer babies.

Cidney Bowman, wildlife passage coordinator with ODOT puts it a little more delicately, saying the males in rut are “not paying as much attention.” And because rut means the deer are on the move and because deer are crepuscular — most active at dawn and dusk — this means they are also most likely to be in the road and make contact with your car in the darkness of autumn.

On a map of wildlife collisions in Oregon, the Eugene area doesn’t look too bad. This area looks nothing like spots outside Roseburg, Klamath Falls and Bend, which averaged more than 11 collisions per mile per year. Lane County is more in the two-to-four range.

But that doesn’t mean that roadways aren’t a problem for deer and elk. Bowman points out that I-5 north of Eugene shows up as having no problems at all. That’s because “traffic becomes a barrier,” she says, with cars bumper-to-bumper acting like a wall, and cutting off the animals’ habitat.

“Most of the data is around deer and elk,” Bowman says of animals and roadways. “But it impacts all species.”

Hitting a deer or elk is costly on a number of levels, and the impacts on animals can also be environmentally costly. There’s a loss of hunting revenues, the cost to the state for maintenance crews, the repair and medical bills and finally “the intrinsic value of wildlife.”

People like to see deer walking around, Bowman says.

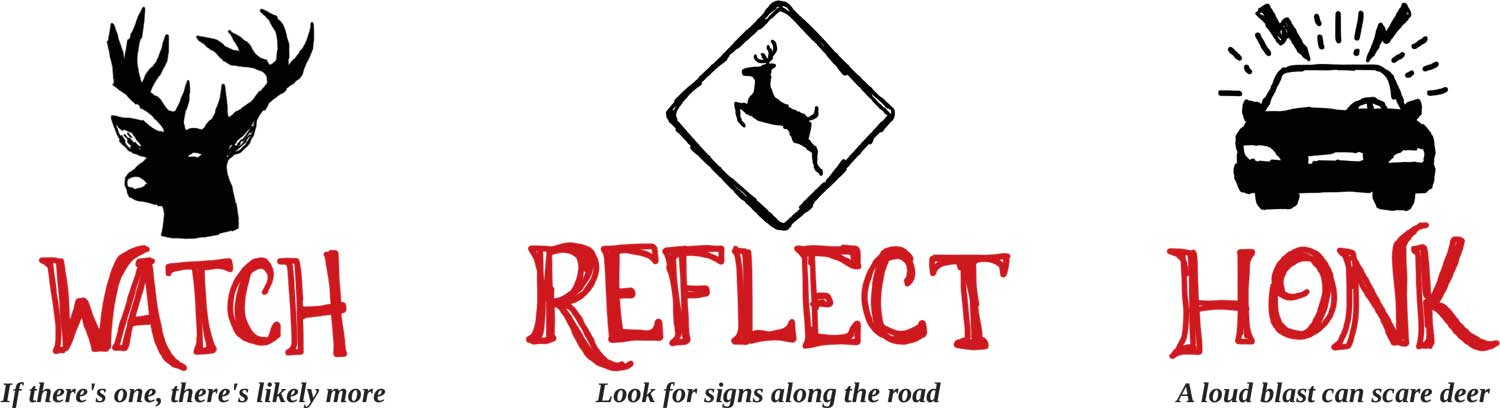

To that end, ODOT’s Wildlife Corridor program, which she says is currently unfunded, revolves around education. That leaping deer sign posted all around Oregon just doesn’t get noticed. “Sign fatigue,” Bowman says.

ODOT has a poster at DMV offices listing the damages as well as advice for avoiding hitting an animal. And Bowman says wildlife overcrossings and undercrossings combined with wildlife fencing to guide animals toward those crossings are 85 percent effective.

And while the beautiful and dramatic crossings in Canada and Washington that you might have seen shared on social media get all the attention, Bowman says current bridges can be converted into pseudo-undercrossings, allowing animals to get across the road unscathed.

Another inexpensive fix is using technology like an animal detection system in which radar triggers a warning light for drivers.

But for you Lane County drivers who don’t want the answer to the question of “Who killed Bambi?” to be “Me!” but who won’t be seeing deer trotting over a wildlife bridge on Marcola Road anytime soon, there are things you can do to avoid creating roadkill.

Bowman says those deer whistles you can buy and mount on your car don’t work. Instead she says, drive carefully and be alert; when possible use your highbeams — the light will reflect off an animal’s eyes — and when you see a deer, honk to spook them to move. Finally, don’t swerve, hit your brakes and hit the deer.

The ODOT poster cheerfully adds, “Watch for the rest of the gang. If you’ve seen one, you haven’t seen them all!”

There are good reasons not to swerve, despite it being human nature to most of us to not want to plow into the wildlife. Deer are unpredictable in their movements, and you risk causing a bigger accident by braking, hitting another car, guardrail or tree.

Also, you might want to know that if you swerve and hit something else, then insurance-wise, that will fall under your collision coverage. If you hit the deer, the damage is under comprehensive coverage. According to the Oregon Department of Financial Regulation, your comprehensive deductible is generally lower.

Thanks to the buck I hit, my Jeep was totaled and insurance covered a new (used) car.

Who Ate Bambi?

When it comes to hitting a deer or elk, Michelle Dennehy, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife spokesperson, reminds drivers it is still illegal to purposefully hit an animal. And if you hit and injure a deer and you put it down to alleviate its suffering, “only you can salvage it.”

However if you come across a roadstruck deer someone else has hit, you are OK to salvage it (Tip: make sure it’s fresh). “No one want to see waste,” she says. “If the animal can be used, great.”

Enlarge

Illustration by Sarah Decker

But because Oregon doesn’t have game meat inspection, it’s eat at your own risk. When it comes to eating, “You’re totally on your own,” Dennehy says. And she warns, roadstruck deer are “not always fit to eat.”

Also, you won’t be seeing deer and elk sold at any roadkill cafés anytime soon, because Dennehy says, “roadkilled deer and elk cannot be sold.”

More than two-dozen other states allow the salvaging of roadkill, and talking to many of my friends born and raised in Oregon, it’s clear the law hasn’t stopped them from eating a deer with a little bumper burn. But the new change in law is the result of SB 372, which was passed by the 2017 Oregon State Legislature and goes into place Jan. 1.

If you were thinking, “Hey, this roadkill thing opens up a whole new area of meat-eating for me!” think again. According to ODFW, under Oregon law, the only people who can keep non-deer and elk roadkill are “licensed furtakers,” (hunters and trappers), and even then only animals that are classified as furbearers: bobcat, gray and red fox, marten, muskrat/mink, raccoon, river otter, beavers and some only at certain times of year.

Game animals aside from deer and elk — like bear, cougar, pronghorn, bighorn sheep and Rocky Mountain goat “that are found as roadkill may not be kept by anyone, including licensed hunters,” ODFW says. Basically, this discourages poaching-by-pickup-truck.

On the other hand, if you have an undiscriminating palate, ODFW says, “Unprotected animals can be picked up by anyone. Examples of unprotected animals include coyotes, skunks, nutria, opossum, badger, porcupine, and weasel.”

Let me know if nutria tastes like chicken.

On second thought, don’t.

Venison on the other hand I’ve heard tastes pretty OK. Bowman of ODOT says the animals her agency deals with “are pretty well decimated” after being hit by a semi-truck, as ODOT is dealing with highways. The deer and elk you encounter on county roads “may be in better condition.”

Dennehy says within 24 hours of killing and salvaging your deer, you need to go online with ODFW and fill out a free permit. This actually could help Bowman in her research as this could yield more data on the animals being struck.

For those pondering salvaging a deer and eating it, you probably won’t mind cutting off its head considering you are about to butcher the deer. You must surrender the head and antlers of all salvaged animals “to an ODFW office within five business days of taking possession of the carcass.”

So let’s say you’ve taken out the deer (accidently) and you are ready to take advantage of Oregon’s new law.

I called Clint Epps, a professor in Oregon State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. We spoke as he was wrapping up a hunting trip — his daughter had just bagged her first deer.

Epps dove right into the nitty-gritty, and I decided to not tell him I’m more of a tofu-consumer.

“The trick with any large animal is getting it cooled down quickly and getting the viscera out of it,” he tells me over the phone. “Start with a basic field dress: Cut around the anus to separate the large intestine,” which you can tie off with grass or string, then “flip it belly up and unzip from the pelvis to the start of ribs.”

You’ll want to start with a knife with a sharp tip, and avoid cutting into the rumen or intestines and getting digesta everywhere, Epps says. If you do, “it’s not the end of the world,” as long as you clean it off.

“Cut the diaphragm away, snake your hand into chest cavity and work in the other hand with knife and cut trachea and esophagus,” he explains. “At that point the whole mass can be guided out.” When that’s done, he says, “You have reduced the weight of the animal significantly.”

Since under the new Oregon law you can’t leave the gut pile on the side of the road and the right of way, you do have to take that pile away with you. And unsurprisingly, you need to get your salvage operation out of the way, too.

Epps recommends skinning the animal immediately if the weather is warm. His preferred method is to put a loop around the deer’s neck, hang it and split the hide down the center and the center of the legs.

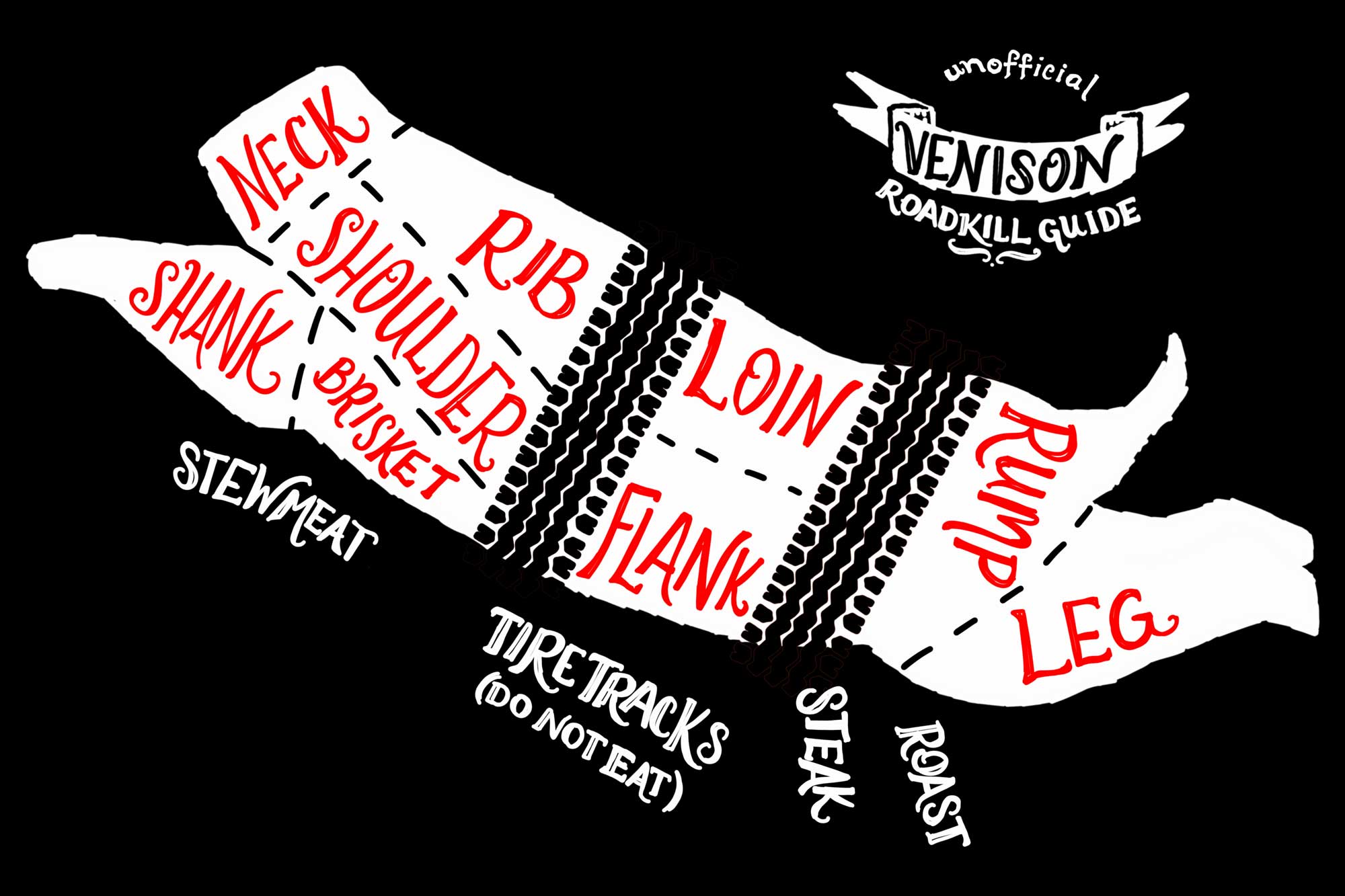

When it comes to butchery, Epps says, “You can talk to 20 different hunters who have 20 different approaches.”

He also points out, and I verified that the first time roadkill butcher can learn about the process by watching a surprisingly large number of YouTube videos showing the deer butchering process.

“My butchery is all seam cut,” he says, meaning he preserves individual muscles or muscle groups rather than chopping the meat all up. “I remove muscles whole because they can be cooked whole.”

At this point, he says, “I do something pretty irregular. I put it in a mild saltwater solution for a couple days; it draws out the blood and reduces gamey flavor.” He then wraps and labels it.

“I know hunters who have the whole thing made into pepperoni because they don’t like to cook,” he says.

Epps, on the other hand, apparently does like to cook.

Enlarge

Illustration by Sarah Decker

He recommends boning out the neck meat, “which makes a fine chili,” cubing it and sautéing it with hot oil, garlic, onions, garlic and “all the spices,” then adding canned tomatoes and stock. Turn down the heat, Epps says, and “walk away.”

Backstrap he sears in a cast iron skillet. Shank meat can be boned out or cooked with the bone in a crockpot or Dutch oven “low and slow” so the connective tissue and sinew “turns into butter.”

When it comes to deer fat, he says try it first and see if you like it. It’s thick and sticky, a hard fat that gets solid when cold. He prefers to slice it off and use pork fat instead if he’s grinding the venison up. Because of the fat issue, for ribs (if they can be salvaged, since you hit the deer with a car, after all) he suggests cooking in the oven or crockpot then grilling and eating hot.

Overall, if you are going to butcher your own deer, he says practice basic food safety and keep your knife clean and sharp.

“Believe me, it’s daunting when you get one of these things in your hands,” Epps says of deer carcasses. “But if you mess up the cuts and they are all ragged, so what? You will do better next time.”

On a final note, as a hunter, Epps makes a point of using every part of the animal he kills, but for roadkill, “cars do a number on them.” If there is blood-damaged or bruised meat, don’t use it.

And remember, ODFW says, “The state of Oregon is not liable for any loss or damage arising from the recovery, possession, use, transport or consumption of deer or elk salvaged.”

Good luck. I’m hoping never to hit another deer, but if I do, let me know if you want to eat it.