“When I first moved here, ferns grew six feet high,” Eugene poet Maxine Scates says in a phone interview. “The ferns are all gone now. When I first moved here the sky was thick with trees.”

The trees Scates is talking about have since come down, “many of them in the storm I reference in the book — the ice storm in 2016.”

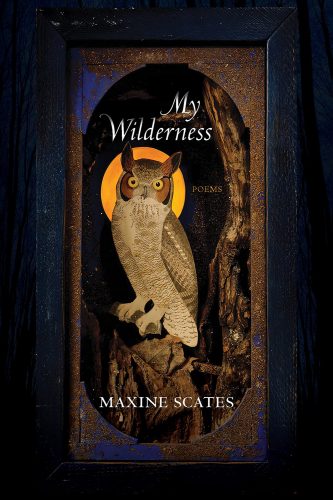

Scates’ book My Wilderness, released Oct. 12, examines nature, particularly the life and death of trees, with both acute transparency and boundless association with the world as she sees it. She looks at the changing forest from the most intimate viewpoint: her own home.

“I’ve lived in this house and on this hill for almost 50 years,” Scates says. “I’ve had a chance to watch the way things have changed over the years.”

Though many of her poems engage with the loss of the forest, she also homes in on the cycles in nature, which she observes to be both comfortingly predictable and beautifully unpredictable. Her poems hold close the nature which is present in her life — “the outstretched branches holding candelabras” and the “leaves trembling” before the rain.

“I feel so lucky. I grew up in a housing tract by LAX, so I know what it is to live in areas where there aren’t a lot of trees. And I know how it affects people when they don’t have them.”

My Wilderness also explores themes of listening and of waiting, both of which Scates enters into through her perception of nature. As she delves into the root of these themes, she ponders the roles of listening and waiting in her writing process.

“I have a designated period of time where I can sit, and I can read poetry or journal, as a preparation for writing. And if nothing comes, nothing comes. But I was here, and I was waiting. And I think that that’s a really important part of any writer’s life.”

Returning to the theme of listening in her work, Scates explains, “I spent so many years listening to both of my parents. And when they passed — when both of them were dying — they had to listen to me for the first time, I felt.”

The book holds a whole sequence of poems written on her mother’s death, including “Eight Days,” which begins by addressing her mother on her 100th birthday, when her mother was still alive. Of the many poems for her mother, Scates says, “That was the poem that needed to be addressed to her.” She explains what comes of writing to someone “is an increased sense of intimacy, and urgency.”

Many of Scates’ poems address someone close to her. The poem “ER” was written to her husband, Bill Cadbury. “My husband was ill at a certain point,” she explains. “We go to the emergency room, and it just feels like the right moment to address him directly.”

Scates also writes from dreams she has, often dreams of friends who have passed.

“I arrived by boat in a dream,” Scates’ poem “Storm” begins, leading us into a dream she had of “a dear friend… maybe a week or two before she died.”

Writing from dreams of those who have died is a part of mourning for Scates.

“I think when you lose somebody, and you dream about them, you’ve got to trust that because that’s really what you’ve got left at that point of their presence. I mean, you’ve got memory, of course, but there’s a presence [in dreams].”

Trust is a vital element in Scates’ writing, both as she begins and in her decision to leave a poem be. “I don’t want to know what I’m writing about before I sit down to write,” she says. “I have a sort of paradigm for it — what I call the arc of the poem. Where I sit down, I want to be absolutely as receptive as I can be. And the poem is sort of ascending at that point. I’m going to sit there until I feel like I’ve written everything to write. That I’ve followed the associations that I need to follow. And it’s a pretty intuitive thing to know whether or not you’ve reached that.”

“I’m delighted to feel like that phrase you read welcomes the reader in.” Scates goes on to tell me after I read a line from “The Oaks” which looks at the aligning and diverging fates of oaks in various places she knows “because [that line] is there for a reason.”

Just as she does not plan what she will write, Scates has not planned ahead what she will read at her reading of My Wilderness, but attendees can expect poems that “give people a sense of the span of the book.” Joining her will be Frank Rossini, who will read from his book Last Confession, released in April. Scates and Rossini attended UO’s graduate program together in the mid-70s. The reading is at Tsunami Books, 2585 Willamette Street, 2 pm Sunday, Oct. 17. FREE.